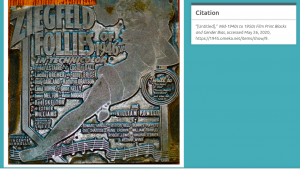

During the Spring 2020 semester, I researched and examined types of gender bias that could have been used in advertisements to promote and sell tickets Classic Hollywood films from the 1940’s to the 1950’s. For this research, I focused on a collection of film print blocks from Galena, IL, that were deteriorating due to poor storage conditions. The first step involved figuring out a research argument that I could present with the collection that needed preservation. With colleagues in my department (School of Library and Information Science) and my advisor I discussed multiple avenues I could take and decided to focus on potential gender bias found in the graphic designs used in the print blocks. Through my research and studying the images of the print blocks, I concluded that the ads did use multiple stereotypes of genders to promote these movies, and these tactics were similar to other ads that used gender bias.

Besides understanding gender bias in this media format, providing digital surrogates for each film block will not only help to preserve the print blocks, but will archive and provide future access to these objects. I worked on this process through the Digital Humanities Capstone Project with the help of Nikki White (the Omeka specialist) and Ethan DeGross (researcher and developer) of the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio. Both Nikki and Ethan suggested that I utilize the content management system, Omeka, for this collection and idea. The Omeka platform has been beneficial for organizing, archiving, and presenting the digital surrogates and applicable data. In further detail, this database is bonded to Dublin Core (DC), which is a schema using vocabulary terms. These terms can then be used to describe digital resources, such as images and surrogates for artwork objects, which ultimately help to make Omeka an ideal environment for the photographs I took of the print film blocks because these terms can help access the digital objects. Figure 1 to 3, shown below, display the front end of my website that I started for my research and archival collection. Titles are not evident because I still need to import my spreadsheet data.

The second step was to address the deterioration of film blocks caused the engraved and etched graphic designs in the zinc plates to fade. Due to their poor storage environment they needed a preservation plan. This plan evaluated the conditions of the print blocks, which incorporated a fun challenge to clean, resurface, and photograph each print block, and then editing each image. The third step to my project was applying my research to classify and categorize the gender bias representation displayed in the print-blocks. From my references, which are listed at the end of this blog, the peer-reviewed research articles by Morris, and Timke and O’Barr have been the most applicable in defining the classification that could be applied to this collection. The final steps involve bringing my collection and research to light through Omeka. Having this experience is giving me the opportunity to work in and learn multiple technical aspects that need to be understood to archive a digital collection.

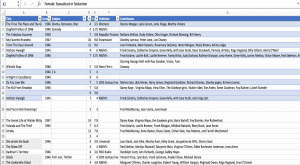

In order to properly archive the object, I have been working in Excel and learning the process of building a spreadsheet. Soon, I will be undertaking the process of importing my spreadsheet into Omeka. Through this project I have not only had an opportunity to play in photoshop, but to develop a metadata schema, which includes figuring out which elements to use in Omeka and mapping the DC suggested terms to best describe my project. I was able to achieve this during the COVID pandemic and the online environment, by emailing Nikki because she was able to assist me on how I could translate my data into the fifteen standard DC fields through examples and recommendations she was able to provide from her professional experience. I supplemented my learning experience through information provided in Omeka, which noted that my field labels in my spreadsheet should match the fields used by DC; therefore, I changed the labels I was using in the spreadsheet to match the specific ones listed in Omeka. For example, I choose that the genre of each film would map to “DC Subject”, height dimensions and Length Dimensions to “DC Formats”, production company to “DC Publisher”, actors to “DC Contributor”, Producer and Director to “DC Creator/s”, promotional quotes to “DC Description1”, image description to “DC Description2”, gender bias editorial classification to “DC Description3”. These examples are shown below in Figures 4 to 7. I will add in the numbers assigned to each print block by owner to the DC Identifier after I can physically go double check what numbers the owner wrote on the back of the blocks.

Besides determining which fields to use for categorization and how to use them for this collection, I had a couple of other option to consider. I could either have each gender bias be its own collection and have eight different collections, or keep the print collection as one whole collection. As the collection stands, I have a total of three different types/classifications for females and three for males, and two other small groups, which represent no bias or a reversal of stereotypical gender roles. However, due to the smaller size of the whole collection and the fact that collections of objects are usually best grouped by some kind of inherent quality, such as shared provenance or format, I made the editorial decision to keep the collection as one and to not only use tags to account for the differences in the gender bias but included them as editorial comments in a description field. The editorial comments referencing the gender biases are listed in the tag and description2 fields, which are shown in Figure 6.

Furthermore, if I had selected the method with eight different collections, I would have had to do eight different spreadsheets and imports. Having eight different collections would add unneeded work to this smaller collection. I felt the best practice for this project would be to have my editorial commentary encoded in its item descriptions and tagging. I feel that having the editorial comments included in the metadata, that my research argument will be apparent in collection.

However, currently (as I alluded to earlier), I am still in the process of trying to learn how to import my spreadsheet as a CSV file because I am not able to save my spreadsheet as a CSV, as suggested by Omeka. I will be zooming in with Nikki to learn how to perform this technical aspect of Omeka. Although, I was able to go into the setting of Omeka and defined the following:

- Original Format: Film print blocks from the 1940s to the 1950s, that came from Galena, IL, and found in storage.

- Physical Dimensions: Each original film print block is its own physical size, and the dimensions, which are height and width in inches, are cataloged under the format field for each item.

- Compression: JPEG

- Producer: Traci Bruns, photographer

- Director: Traci Bruns, image editor

- Objective: To display various gender representations of Hollywood film print blocks from the 1940s to 1950s.

Moving beyond that, the next goal I have for this online digital collection is working on the controlled vocabulary aspects for the descriptions I created in the fields. I will incorporate ideas for that from the Getty vocabulary databases. These terms have been generated from the Getty Vocabulary Program, which was created through the Getty Research Institute. This specific vocabulary contains terms, names, and other information about the digital objects, and concepts relating to art, architecture, and material culture. I will use these terms in the data entry stage to help describe the archival materials and visual surrogates, which will help solve the challenge of describing the images within this digital archive. To manage the subjective aspects of descriptive metadata I plan on adding URLs in the metadata, which will link to similar material that will provide related images and ads of the films.

Lastly, I know I have a lot more work that needs to be done on this project, but am excited to learn more as I move forward. I hope to be able to find and connect to other digital gender studies and/or print blocks for films or other general newspaper ads to explore different avenues, share data, and to help ideas exist beyond traditional teaching or archival methods. Also, in conclusion, preservation and archival projects like the project I have been creating are even more relevant in today’s society as we have been transitioning to more virtual environments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital collections not only provide more access in general, but allow archival collections and ideas to reach to a broader audience. Furthermore, concepts within and through digital humanities formats provide other forms of pedagogical moments, which help to advance creativity and new ways of teaching and understanding our past and our world. More specifically, having this experience through Capstone and working on my own archival collection has provided a great foundation to work on other similar preservation projects and I will be able to apply what I learned to other digital platforms.

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

References for the Gender Bias Classification:

Green, Denise N. “Fashion and Fearlessness in the Wharton Studio’s Silent Film Serials, 1914–1918.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 60, no. 1 (2019): 83-115. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/724745.

Morris, Pamela. “Overexposed: Issues of Public Gender Imaging.” Advertising & Society Review 6, no. 3 (2005) doi:10.1353/asr.2006.0003.

O’Barr, William M. “High Culture/Low Culture: Advertising in Literature, Art, Film, and Popular Culture.” Advertising & Society Review 7, no. 1 (2006) doi:10.1353/asr.2006.0020.

Timke, Edward, and William M. O’Barr. “Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertising.” Advertising & Society Review 17, no. 3 (2017) doi:10.1353/asr.2017.0004.

Wood, Bethany. “Gentlemen Prefer Adaptations: Addressing Industry and Gender in Adaptation Studies.” Theatre Journal 66, no. 4 (2014): 559-579. doi:10.1353/tj.2014.0120.

-Traci Bruns