Antecedents

In 1987, Congress amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (1982) designating Yucca Mountain as the sole nuclear waste repository for the country. Still reeling from the Three Mile Island accident (1979), fears of an American Chernobyl (1986), and cinematic representations of nuclear crises in movies like The China Syndrome (1979) and Silkwood (1983), the majority of United States citizens adopted a Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) attitude towards nuclear waste storage. When the dust cleared, the final tally was 49 states to 1 in favor of the proposed repository. The sole dissenting vote was cast by Nevada. Fear caused an entire nation to enforce its will on a minority of its citizens.

Fast-forward to May 10, 2018. Forty-one years after the passing of the original amendments, the House of Representatives approved with a vote of 206-179, HR3053, the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 2018, seeking to relicense and fund the Yucca Mountain facility. After forty-one years of relatively safe on-site nuclear waste storage at both former and operational nuclear power plants, the NIMBY arguments of yesterday do not command the same potency they once held. The real danger now lies in disturbing this waste, in transporting it thousands of miles away, through thousands of backyards. My project seeks to illuminate and make visible the risks involved in nuclear waste transportation to Yucca Mountain should the repository be officially opened.

Project Goals

Heading into this project, I envisioned three stages of development:

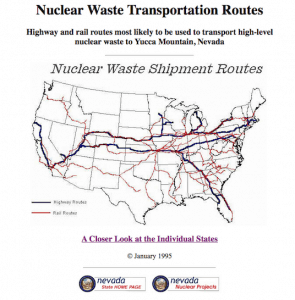

- Creating an interactive map of nuclear waste transportation routes by rail and highway based on the 1995 transportation maps produced by Nevada.

- Upload the interactive map to a website and make it available to the public.

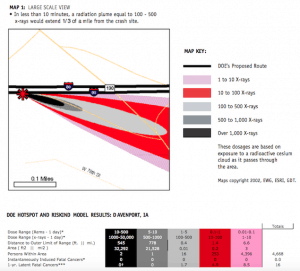

- Import real-time weather conditions and upload HOTSPOT, a radiation modeling program developed Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Should the Yucca Mountain project proceed, I hope to develop this last stage into an application for first responders to use in the inevitable case of a transportation accident.

Development

I’ve used CARTO mapping software in the past with varying degrees of success, so I chose to build this current iteration in ArcGIS. I have never used it and wanted to become familiar with some of its features and capabilities. < —- IMPORTANT —- KNOW THE REQUIREMENTS OF YOUR SOFTWARE BEFORE YOU BEGIN —- > ArcGIS doesn’t run natively on Macintosh. There are work-arounds like running ArcGIS through Windows in Boot Camp or using utilizing a virtualization program like Parallels.[1] Neither of these, however, were options for me. And having no prior experience with the program, I erroneously signed up for lab time on one of the Studio’s Macintosh computers. Fortunately the lab has plenty of Windows-based computers that I can “float” between when not in use. < —- IMPORTANT —- KNOW THE LIMITATIONS OF YOUR HARDWARE BEFORE YOU BEGIN —- > ArcGIS doesn’t store geodata, it retrieves it from wherever you save it. When using CARTO for another class, I saved my data to the desktop. There is a way to save it to one’s UIOWA (account/username?), but my initial geodata was already saved to a flash drive so I began saving all of my subsequent shapefiles and layers to my 8 GB flash drive. About halfway through Stage 1, I needed to download the US Census TIGER Roads National Geodatabase, a 2.4 GB file of which I had only about 1.7 GB of available space. I now have a 64 GB dedicated flash drive for this project, but I had to transfer all previous data to the new drive before I could use it in ArcGIS.

That about covers the initial lessons I learned. I’ve learned a few more since then, but I will save these for my next post on the production process.

Best,

G. Gregory Rozsa

Ph.D. Candidate

American Studies

[1] https://www.esri.com/arcgis-blog/products/arcgis-pro/3d-gis/arcgis-pro-in-mac-os-x/