It’s early July, which in the library world means post-ALA. I was one of over 21,000 attendees to descend on Washington D.C. and the American Library Association annual conference. For a Digital Initiatives Librarian, the selection of sessions and meetings at the conference is not as broad as for public librarians, school librarians and other academic librarians, but one group I have enjoyed meeting with for the last two years is the JPEG2000 Interest Group.

What is JPEG2000? JPEG2000 (aka JP2 or J2K) is a digital image format developed to be the next generation image format. Slow to be generally adopted, JP2 may not fully replace JPEG as the standard compressed image format or TIFF as the standard archival image format, but rather be a third option. JP2’s strength is in its flexibility: it can be uncompressed like a TIFF or compressed like a JPEG, although when compressed, its quality is much higher than a JPEG due to the wavelet compression technology on which JP2 is based.

OK, enough techno-speak. The main topic of discussion at the interest group meeting was whether JPEG2000 should actually replace TIFF as the preferred archival image format for digital library initiatives. Far from being a settled issue, some leading institutions such as the California Digital Library have made the switch completely, while the Digital Library Federation still recommends TIFF as the archival format. Some attendees of the interest group such as Harvard weren’t even at liberty to discuss the decisions they’ve made due to their mass digitization program agreements with Google.

A sub-issue was whether switching to JPEG2000 and its smaller file size would allow more full-color scanning of textual materials, which is central to the debate between the importance of the content vs. the artifact. I.e., is it enough to scan a diary in grayscale to capture just the content, or should full-color scanning be employed to capture the color of the page, the color of the ink, and therefore a truer representation of the artifact. There are those that feel strongly on both sides, but the adoption of JPEG2000 may allow content and artifact to live together in harmony.

An interesting side note to the discussion of digital images is that a motion JPEG2000 format has also been developed motion pictures, and the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) has already selected the format for direct transmission to cinemas. (No indication yet as to when we’ll say goodbye to film reels and hello to 1’s and 0’s).

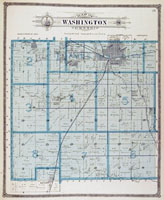

Like many other digital libraries, here at Iowa, we have been using JPEG2000 primarily for map images, where we want to display a high resolution image at a smaller file size. We may however be a long way off from adopting JPEG2000 as the archival format for all of our digitization activities and throwing away the TIFFs.

All in all, meeting with this small group of a dozen people and discussing how the slow adoption of JPEG2000 will impact our work was rewarding in ways that the huge lecture sessions at

ALA were not. I hope future ALA conferences will include more of these interest groups for digital initiatives librarians, but I’ll always make room on my schedule for this one.

–Mark F. Anderson

Digital Initiatives Librarian