By Gary Frost

An example of the binding discussed below is also available under the title “Replica of the Stonyhurst Gospel” in the Book Model Collection on Iowa Digital Library.

Binding description

This small book (137 mm x 95 mm) known as the St. Cuthbert Gospel has witnessed many turbulent eras of English history. It has survived to enjoy modern veneration and security in the British Library. It has experienced many previous eras beginning with its construction (c. 700-c. 730) in a monastic scriptorium at the beginning of the medieval period. During the medieval era it was sequestered in the coffin of St. Cuthbert. The book then miraculously survived turbulence and monastic library destruction of the English Reformation and Counter Reformation. Next the Gospel survived secular turbulences of antiquarian ownership and college librarianship. Only in the twentieth century did the Gospel attract paleographic and book craft study and a more secure future.

The process of replica making of the St. Cuthbert Gospel binding offers its own approach to book craft study since it reenacts methods and suggests insights into monastic book binding methods of late Antiquity. During the Insular period, it is possible to situate the binding in a wide context of influences afforded by monastic exchange, communication and travel. Stylistic, paleographic and technical influences of the book and binding can be attributed to a diversity of Mediterranean cultures. Perennial handcraft methods and expertise are also represented by the Gospel. Timeless craft skill was needed to confront challenges of the binding scale, shape and symmetry.

Craft finesse is needed when working at such a small size. The secondary endbands of the Gospel as worked through the end caps required clean and even piercings less than two mm apart to avoid perforation tearing. The use of a tertiary support stitching at the spine head (and not at the tail) may well represent a reinforcement repair needed to stop end cap tearing during binding. Thinness and beveling of the wooden boards also required close selection and hewing to avoid breakage. Thin thread making required careful fiber selection and spinning. Refined tools and needles were required. A small metal burnisher and stylus was also needed.

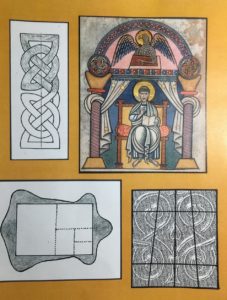

Pages and binding shape must be adapted to the small “pocket” Gospel size. Cutting-out the bi-folios from parchment imposes a squat page shape derived from proportions of the skin. A large service book would require use of a whole skin for each bi-folio of four pages. The next division would provide two bi-folios, then four or then eight bi-folios from subsequent divisions all of which yield the same squat page shape exemplified by the St, Cuthbert Gospel with a height to width ratio of 1.5 : 1. (see illustration) “A striking consistency from one end of the Anglo-Saxon period to the other and from one end of the country to the other.” can actually be explained by characterizing the squat shapes of any bi-folio pages cut from parchment skins.[1]

Another timeless challenge for the binder is symmetry. Various methods are conjectured for impression methods used to produce the Tree of Life motif on the upper board of the St. Cuthbert Gospel. This discussion should start by considering the motif symmetry within a square frame. (see illustration) Whether use of an impression blocking matrix or construction of an underlying raised matrix, both methods would require transfer, modeling and decorating of a deliberate symmetry.[2] The previous proportions of size and shape also interplay with the motif symmetry. A magnificent craft command was needed to render this relief ornament.

Turning to consider the upper of two lacing design panels, Nicholas Pickwoad mentions, “If the intention was to ensure a symmetrical design, it failed.”[3] This remark opens a space for discussion of a potential of an error of error. There are two panels with laced designs. The bottom panel is symmetrical, left and right, both in the mirrored lacing and in color contrast. The top panel is not, neither in the lacing pattern or in the coloring. The twenty first century issue may be that we see the asymmetrical design as deficient.

For the eighth century crafts person design was all earthly performance. The perceptual clue is an odd terminal lacing figure. Three lacing terminals are up right but the left figure of the top panel is twisted. It could have conformed by flipping. The panel design has a different maneuver in space and a different asymmetric is at work. There was once a sense of earthly discrepancy and Heavenly perfection. A nagging discouragement in this life continues. We add anxiety of anxiety. The craft worker in the monastery workshops of Cuthbert and Benedict knew no mechanized uniformity or automated verification. Earthly discrepancy was assimilated as a space where demons interplay.

Binding performance

A vindication of the crucial role of binding for book functionality is revealed by comparative performance of St. Cuthbert Gospel and its recent British Library publication of studies of the book.[4] Both have been damaged in use, one by thirteen centuries of turbulent history and the other by a few weeks of reference. The juxtaposition becomes even more bizarre and relevant since the modern reference book provides an anthology of expert studies that still manages a disregard of the character, quality and performance of the Gospel artifact.

The burst bound modern book, “printed in Malta by the Gutenberg Press” is off-set production imposed in “32nds” in orientation of a duplex, color run. The wrong-grain gatherings were notched and adhesively bound but the coated paper stock resisted bonding and reference opening and the bi-folios progressively detach from the injected adhesive. Adding a bit more disconcerting for description of the hand-held original binding is the editorial convention of reference to the “right and the left” cover.[5] Better for binding description would have been Clarkson terms of “upper and lower” cover. Disorienting as well, the modern book provides no one-to-one reproductions; they are all either too large or too small and materially misfit the Gospel. The eighth century book is its own best exemplar.

A replica binding project at least enforces the scale, shape and symmetry of the Gospel artifact. It requires manipulative familiarity and (attempted) performance re-enactment of the work of the monastic craft worker. However, there is glaring technological, methodological and even ontological discrepancy and displacement of a modern view and modern replica.

St. Cuthbert Gospel implication

Today we are presumed to be at an advantage over the challenges faced by the eighth century crafts person. We can easily find spools of microscopically fine and uniform linen thread and all varieties of bookbinding supplies can be ordered on-line. But step away for a moment and see another view. Strategic advantages of intuitive experience and assimilated knowledge are at work with the eighth century craft person. We resort to explanation, diagram and supplied materials to re-enact the Gospel endbanding and are then surprised by inept results. The eighth century crafts person already understood sewn margins, blanket stitch edging and reversed seams and there was an experienced knowledge of such constructions in daily use and responding to daily manipulation. Then add the monk’s mind-set capable of merging rhythmical sewing and reading as meditative equivalents. Such advantages greatly out-maneuver the modern endbander.

Of course, the eighth century crafts person could not visualize an off-set, full color book on coated paper and that same person would be mystified that a modern book could not move and perform in an opened field, console in a forest or quickly respond to touch and grip in a storm without coming apart. Such expectation and perceptivity to making and use of a hand-made book is now unknown and many industrialized bindings can fail field testing.

There is a third thing lurking here. Beyond the St. Cuthbert Gospel and the current anthology of studies on the St. Cuthbert Gospel are the many replica models.[6] The St. Cuthbert Gospel is an irresistible exemplar and a popular project for hand bookbinders. I did see the original of the “Stonyhurst College” Gospel through the glare of the glass display case in London, 1980. I have also handled various replicas of the binding. Memorable was the replica by Martha Little made in the workshop of Roger Powell. Martha’s model included the detached board. Other models known to me include one by Bill Anthony and another by Mark Esser now in the University of Iowa Book Model Collection. I will be very curious to look at these again as soon as I complete my own models of the St. Cuthbert Gospel.

The venerable Gospel is breeding its own replicas. These replicas all commemorate a book craft challenge and the extreme rareness of any surviving early book exemplar. Models of the St. Cuthbert Gospel must also commemorate the early books that have not survived. These lost books were the endless civilian causalities of conflict and dire, destructive interventions. These lost books haunt the one surviving St. Cuthbert Gospel and its melancholy recreations.

02.13.2022/glf

Endnotes

[1] Quote citation, p.14, St. Cuthbert Gospel, 2015. A material explanation lurking behind the shape of papyrus, parchment and paper books is the half-square bi-folio cut from the papyrus roll commodity yielding the half-square, elongated book of late Antiquity, the parchment bi-folio cut-out that produces the squat Mediaeval book shape and the ergonomic of the hand paper mold yielding a rectangular book shape.

[2] The impression matrix described by Nicholas Pickwoad used through leather to counter- form underlying clay is associated with other the Anglo-Saxon use of matrix debossing of metal foils. The issue of the distinction of a positive or negative (read-right vs. read wrong) matrix, hard pressing negative areas or hard debossing of positive areas is not discussed. See St. Cuthbert Gospel, (2015), pp.53-55.

[3] The St. Cuthbert Gospel, 2015, p.58.

[4] Breay, Claire and Meehan Bernard, editors, The St. Cuthbert Gospel, Studies on the Insular Manuscript of the Gospel of John, The British Library, London, 2015. Before this publication hand bookbinders referred to the Roxburghe Club publication; Brown, Julian B., The Stonyhurst Gospel of St. John, 1969, with a chapter on the technical description of the binding by Roger Powell and Peter Waters.

[5] The “right vs. left” cover boards may be a UK art history convention that are ambivalent when considering the handled three-dimensional George Stout described object.

[6] Michael Burke taught a workshop in which the students make a St. Cuthbert Gospel binding replica. He credits notes from Martha Little who also taught a workshop at PBI in 1994.