When the first generation of “mill girls,” Yankee farmers’ daughters, arrived in New England’s textile factories in the early 19th-century, they were not completely sure what they would encounter or how much work they would have to do. Two hundred years later as I begin to collect and organize an archive of their writings, I imagine we share similar feelings: uncertainty, anxiety, excitement, and anticipation.

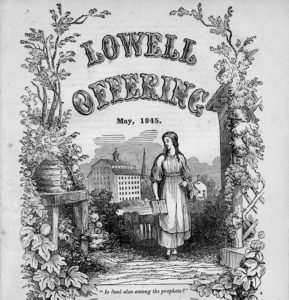

The female operatives had aspirations that extended far beyond the factory walls. For many, the mill served as a launching point where they could pursue other careers or earn extra money to set aside for a future marriage. Many joined “improvement societies,” typically church-sponsored groups that encouraged them to write and discuss literature. Emerging out of one of these societies, the operatives produced a magazine dedicated to their writings: The Lowell Offering. The Offering ran from 1840-45 and quickly came under the editorial control of two operatives: Harriet Farley and Harriot Curtis. Factory owners publicized the magazine, using it to showcase the refinement and education of their workers. Non-mill residents like Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Harriet Martineau (the 19th-century is lousy with Harriets), were impressed by the young women’s literary productions.

The pages of the offering are filled with poems, essays, short stories, editorials, and songs that demonstrate the factory workers’ familiarity with existing popular writing, occasionally crediting their inspiration, and more importantly, their creative experimentation, subverting generic formulas. These women were written about so often, it can be difficult to uncover their own thoughts. Even in discussing the Offering, a lot of time is spent addressing Dickens’s response or attempting to figure out whether the magazine was mill propaganda, and not enough time is spent reading the words of the workers themselves.

My goal this summer is to create an accessible archive of The Lowell Offering and encourage visitors to explore the rich material produced by this remarkable group of women. As I dive into the texts, it is becoming increasingly clear that there are many aspects I failed to consider. I’m currently cataloging and tagging each of the entries in the Offering’s 5-year run, but the variety is simply incredible. I did not expect “death” and “grief” to appear so frequently in a magazine so frequently accused of presenting mill work in too rosy a light. I’m also busy trying to connect authors with their pen names; fortunately, Harriet Hanson Robinson (that’s the fourth Harriet, if you’re counting) produced a key! UNfortunately, some operatives used multiple pen names and some even used the same pen name as another operative! A task I thought would take me at most a long weekend is taking significantly more time. It is challenging, but necessary to create a complete picture of these operatives’ writings.