After familiarizing myself with Mukurtu CMS throughout my Studio fellowship this summer, it became increasingly necessary to address issues of open access, organizational principles, and ethics in building a digital archive for the Transgender Oral History Project of Iowa (TOPI). To learn more about the project, please read my original blog post about my summer work building an archive. Mukurtu is an open access content management system, it is designed for use by indigenous communities and directly responds to issues of tribal knowledge and cultural protocols based on historic and spiritual practices. Recognizing the specific colonial legacies Mukurtu is designed to address, it is clear that a transgender digital archive requires a different code of ethics and access. While both the history of indigenous communities in the U.S. and transgender and gender non-conforming people have been similarly marginalized and rendered invisible, the structures and practices of each archive are inherently different.

It is important to not only recognize that there are different historical legacies marginalizing both indigenous and transgender communities, but it is also crucial to acknowledge the present day differences and how this translates to digital archiving practices. For communities using Mukurtu, they often have a historically defined tribal community whether or not that is federally recognized. Many indigenous communities have their own land and community councils. The significance of this community definition is that the contours of each indigenous community have clear boundaries, membership, and leadership. In contrast, the transgender community has no boundaries and no clearly defined membership or leadership with power. There are certainly community organizations, groups, and nonprofits organized in geographic regions that have a concentration of transgender and gender non-conforming people, but transgender communities are ultimately dispersed.

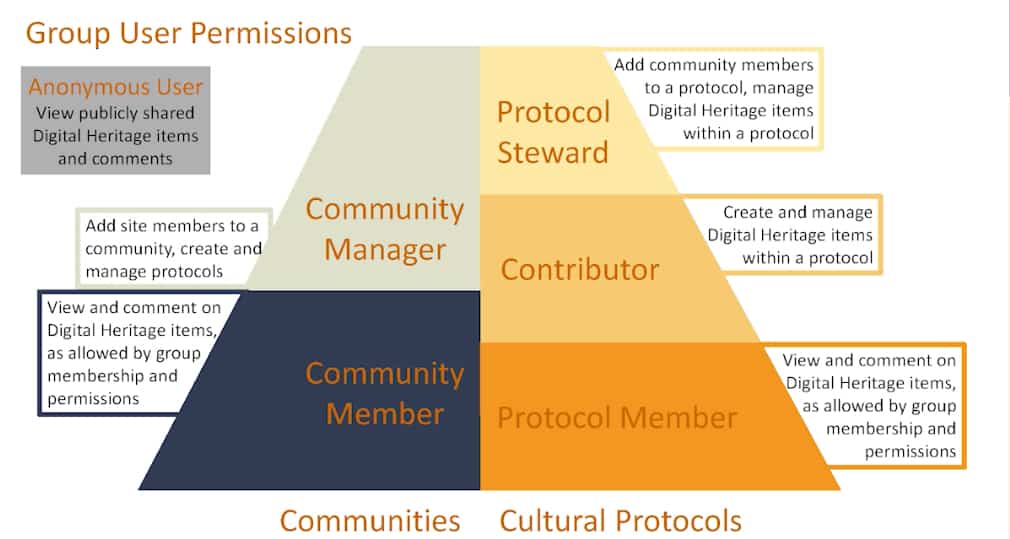

For the design of Mukurtu, indigenous communities are provided full control and the ability to continually edit and alter access protocols. It rests with the leaders and authorities within each community to define and update these protocols. For TOPI, there is no singular community to hand over control of the archive (see figure below for user permissions). Control over access to the digital TOPI archive cannot mirror the control that Mukurtu provides. As an oral history project, TOPI addresses the needs and privacy concerns of the individual interviewees involved in the project. Traditionally, oral histories are either made fully accessible to researchers and to the public immediately, or they are embargoed for either a set number of years or until after an interviewee passes away. The reality for transgender communities is that their history is undervalued by academics and the result is a dearth of archival material and scholarly publications. Recognizing, celebrating, and studying the history of transgender and gender non-conforming people, is a valuable asset to creating a society more accepting of transgender people. The interviews collected for TOPI must be made accessible to the public, to researchers, and to members of the community.

In contrast to the archival practices embedded in the design of Mukurtu that allows indigenous communities to actively control access, the access to archival materials digitized in TOPI’s archive is predetermined. The user permissions and the structure therefore must operate in response to how interviewees define access. For the oral histories collected digitized access will be determined at the point of the interview and verified through the sharing of the written transcription. Interviewees mark off the portions of the interview to be made publicly accessible, accessible to researchers, at a more granular level to the transgender community at large, and even further, portions made accessible to only people who share identity terms with the interviewee.

Navigating this structural logic in by designing an archival space in Mukurtu this summer was a challenge because of how TOPI is taking shape. Considering both indigenous and transgender archives, what is made clear is that open access is not the best practice for communities historically subjected to violence within and outside of the archive. New digital archiving projects force archivists, scholars, and digital humanists to rethink notions of privacy, ethics, and open access.

To keep up with TOPI as the project moves forward and the archive launches, follow us on Twitter @TransIowa. If you want to get involved in the project as an interviewer or interviewee, please email us at transoralhistoryiowa@gmail.com.

To follow my work in the realm of digital public history and community archive building follow me on Twitter @ambettine.

Aiden M. Bettine

Ph.D. Student in History

Master’s Student in Library and Information Science

The University of Iowa