This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Larisa Greway, a museum studies intern at Special Collections and Archives.

If you can read a piece of sheet music, you’ve benefited from over a thousand years of evolution. In the Middle Ages, music not only sounded, but looked much different than it does today. On this whirlwind tour through the medieval music of Special Collections and Archives, we’ll meet a few of the most melodious manuscripts we have to offer.

The development of music notation was a long and complicated process. Most medieval music that we can track the history of is liturgical, meant for use in church. The early liturgy was sung in plainchant, a simple style of chant meant to emphasize the text. Before the ninth century, no pieces of written notation survived. Instead, pieces of music were passed down via oral transmission, and because of this lack of standardization, local variations of chants abounded. But during the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century, interest in music theory began to grow, and the liturgy began to introduce multi-voice polyphony and more complicated settings. Systems of notation soon became necessary to record the new forms of music taking root.

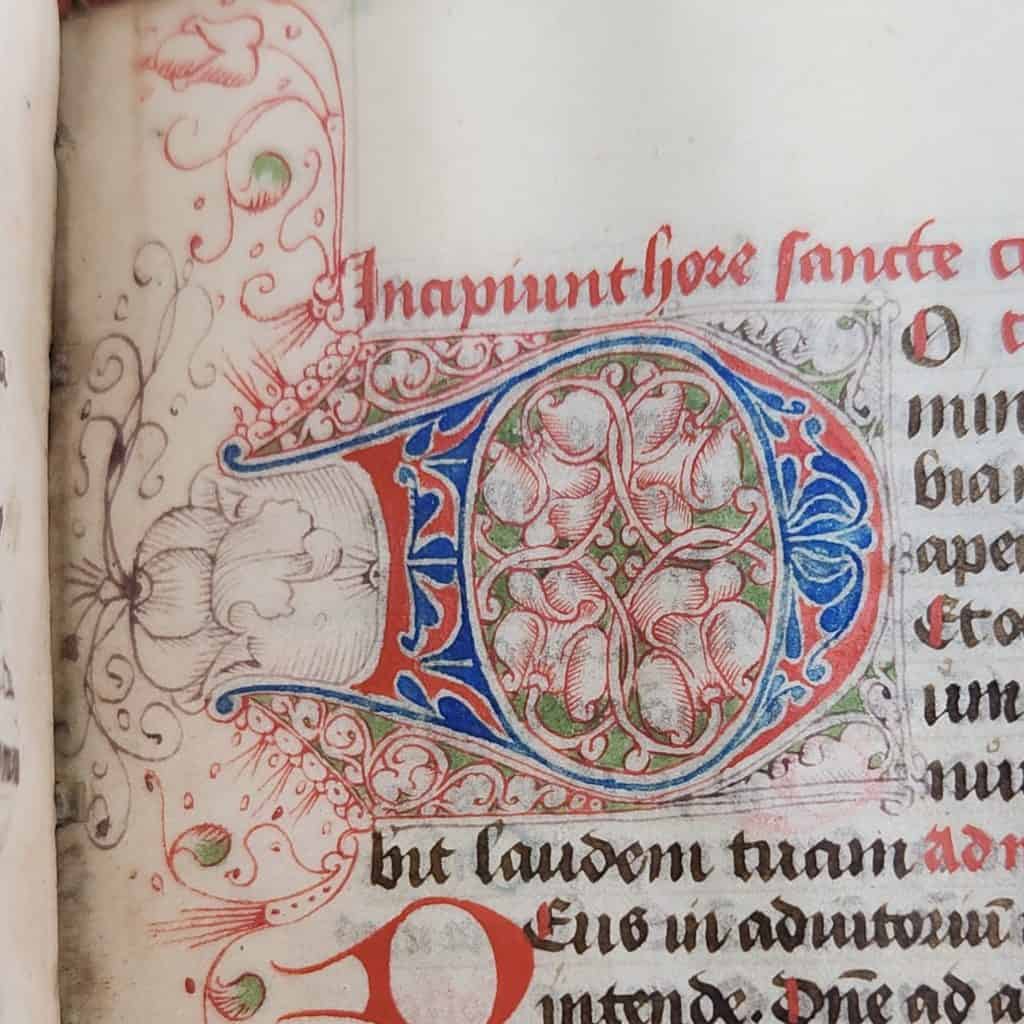

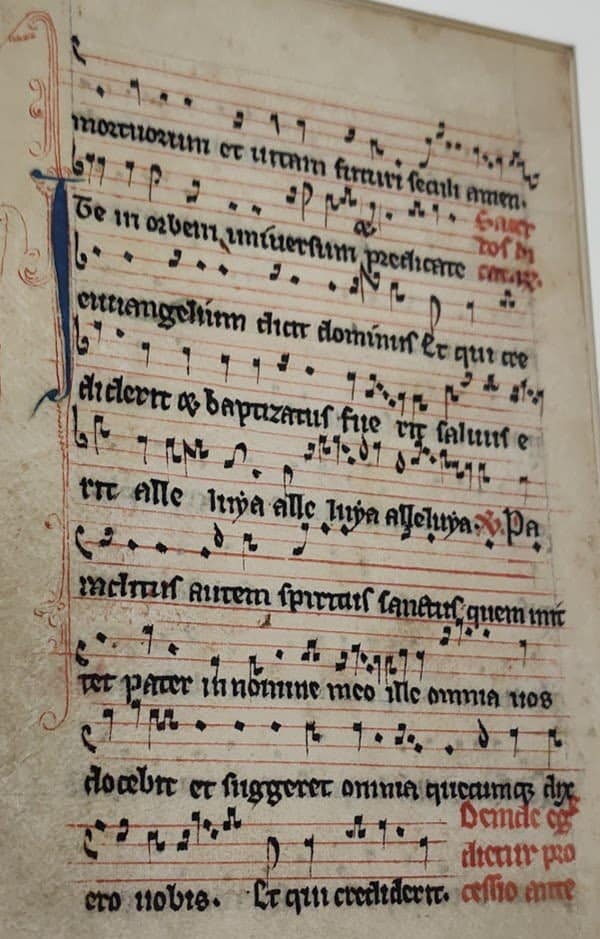

The most popular and enduring system used neumes. Whereas modern musical notes are based on an absolute system of rhythm and pitch, the earliest neumes showed pitch only in relation to each other. Later, heightened neumes were written on four-line staves with added symbols to indicate rhythm. This leaf from a gradual (a book collecting the musical items of the Mass) is the earliest example of neumatic notation in Special Collections and Archives, dating from 1230 in England (fig.1, xfMMs.Gr3).

The neumes are arranged on a staff with base and treble clefs, and the composition is highly melismatic: there are runs of many different notes in quick succession. The short paragraphs in red ink are rubrics, indicating particular directions to the celebrant of the Mass.

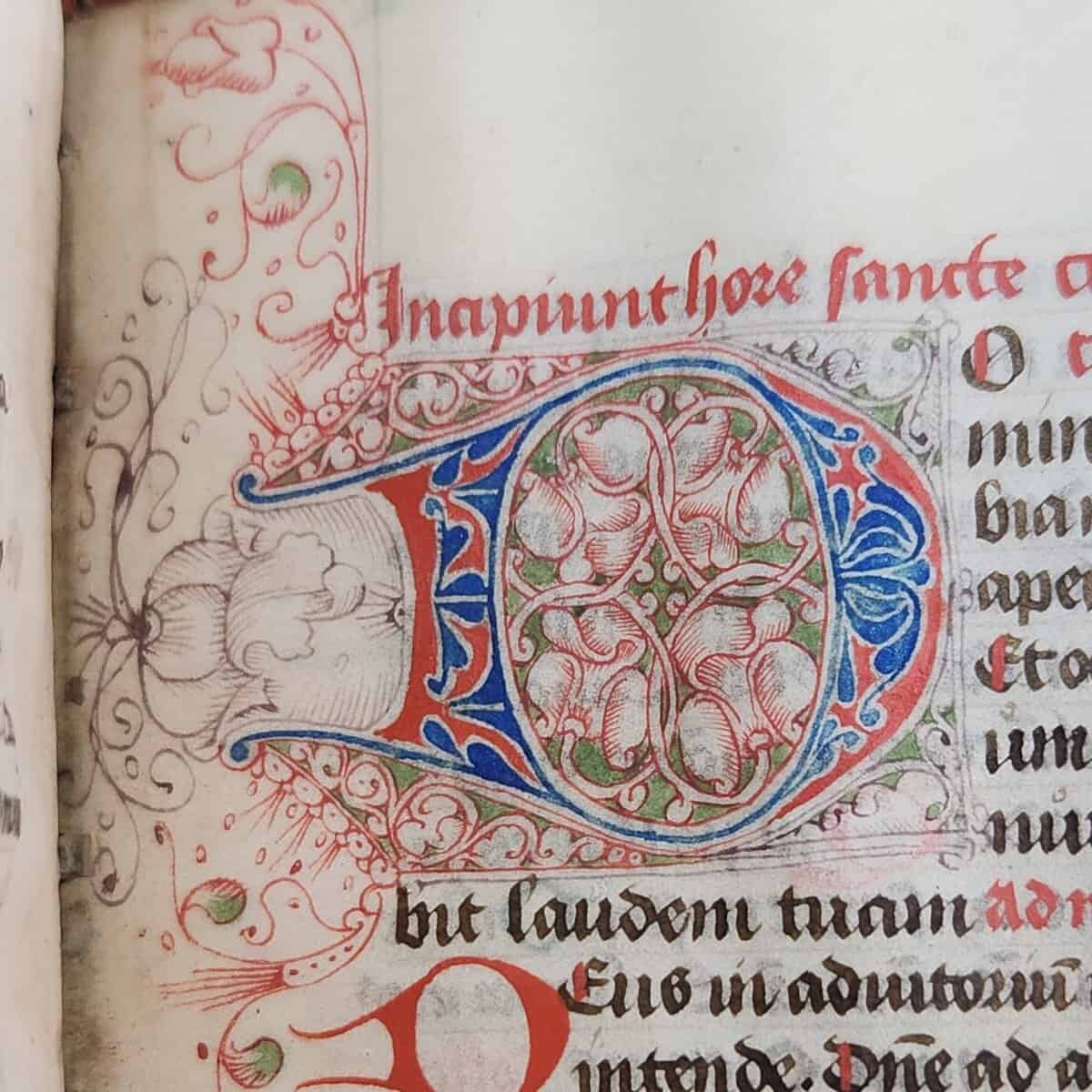

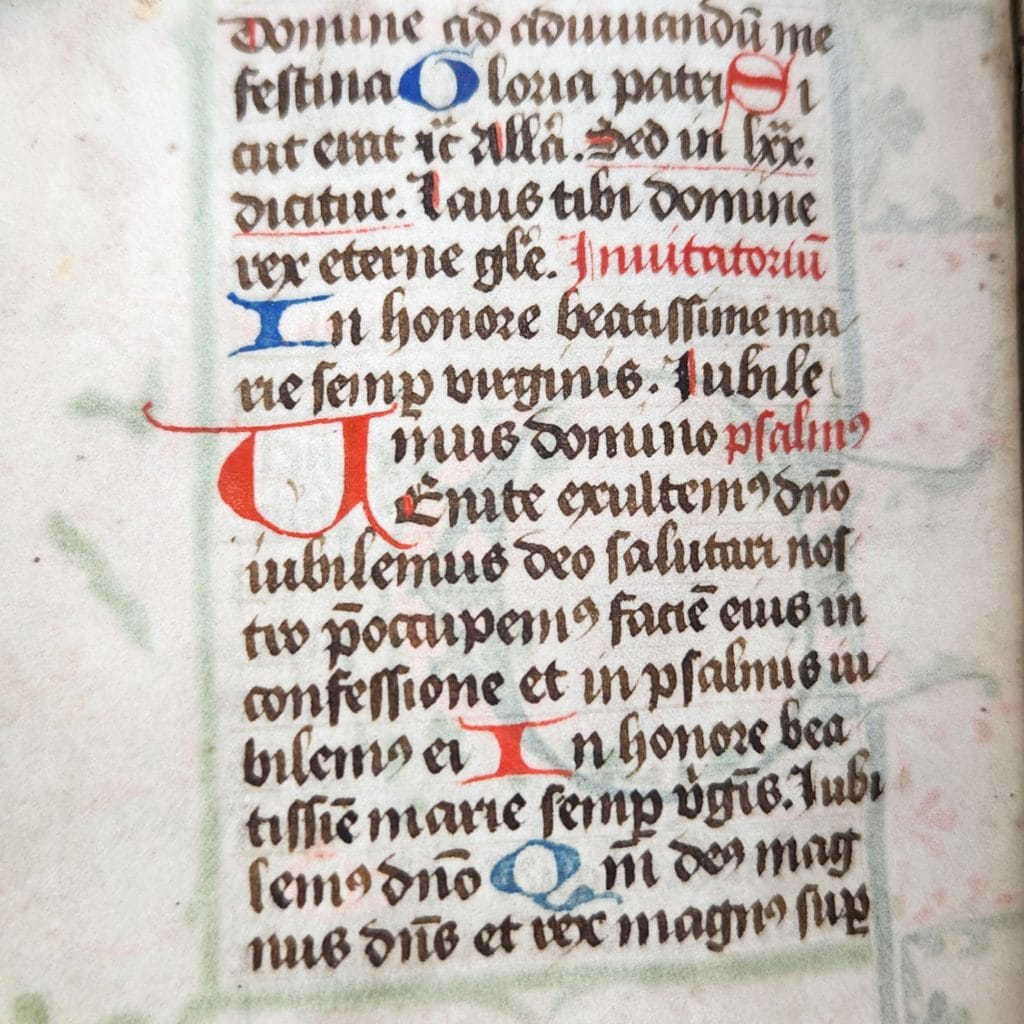

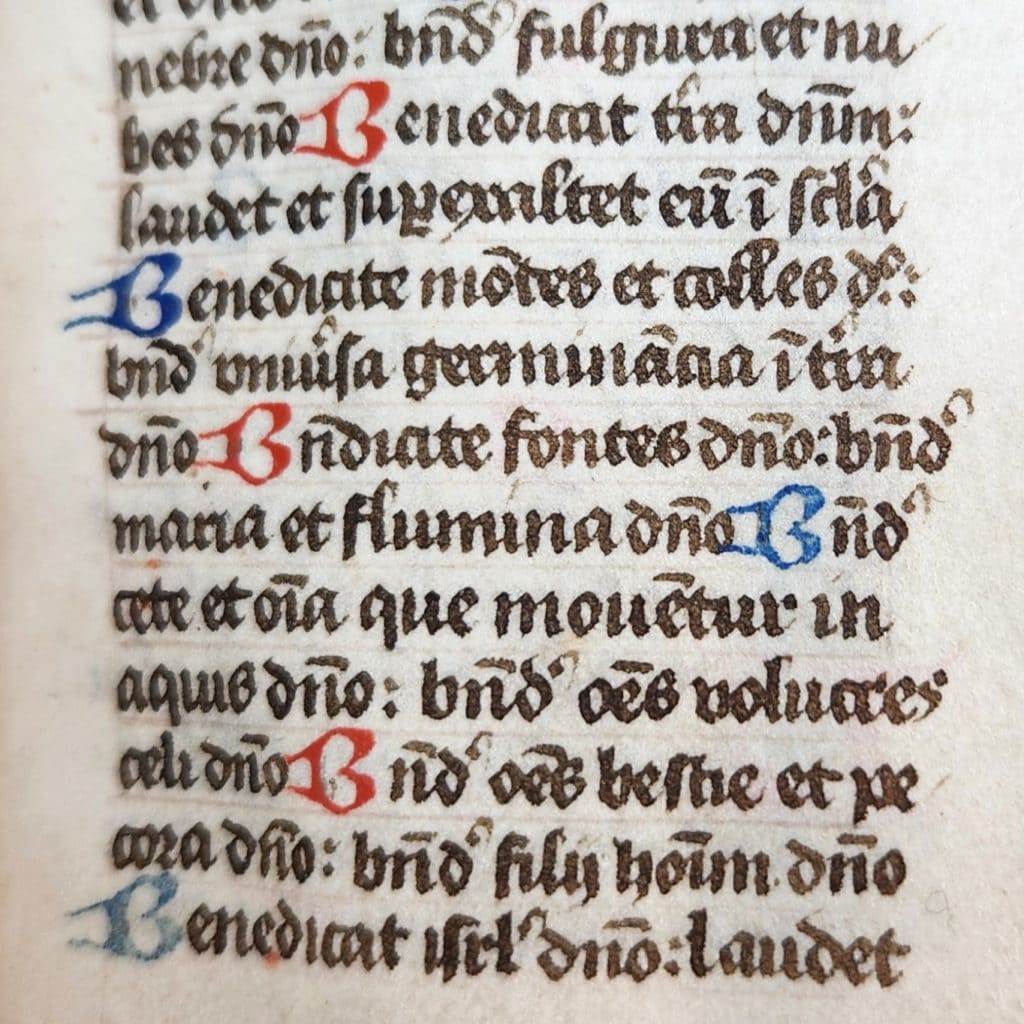

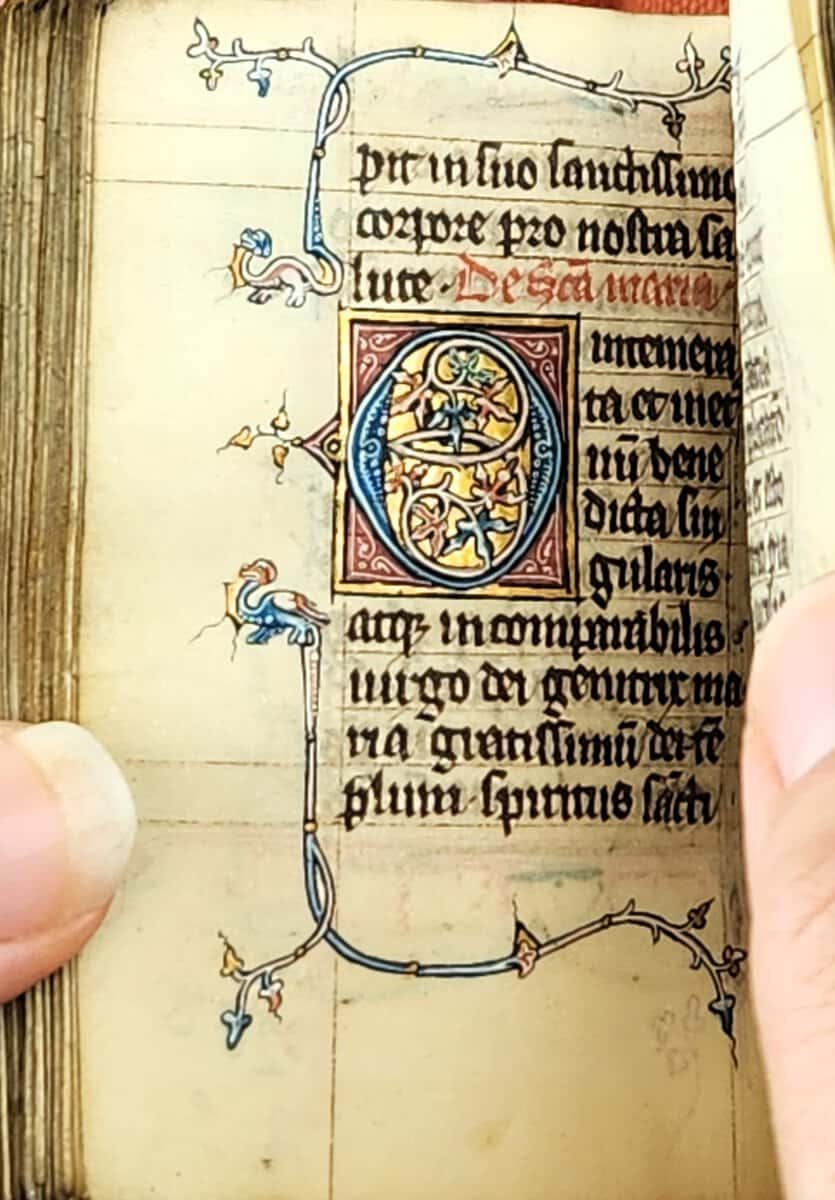

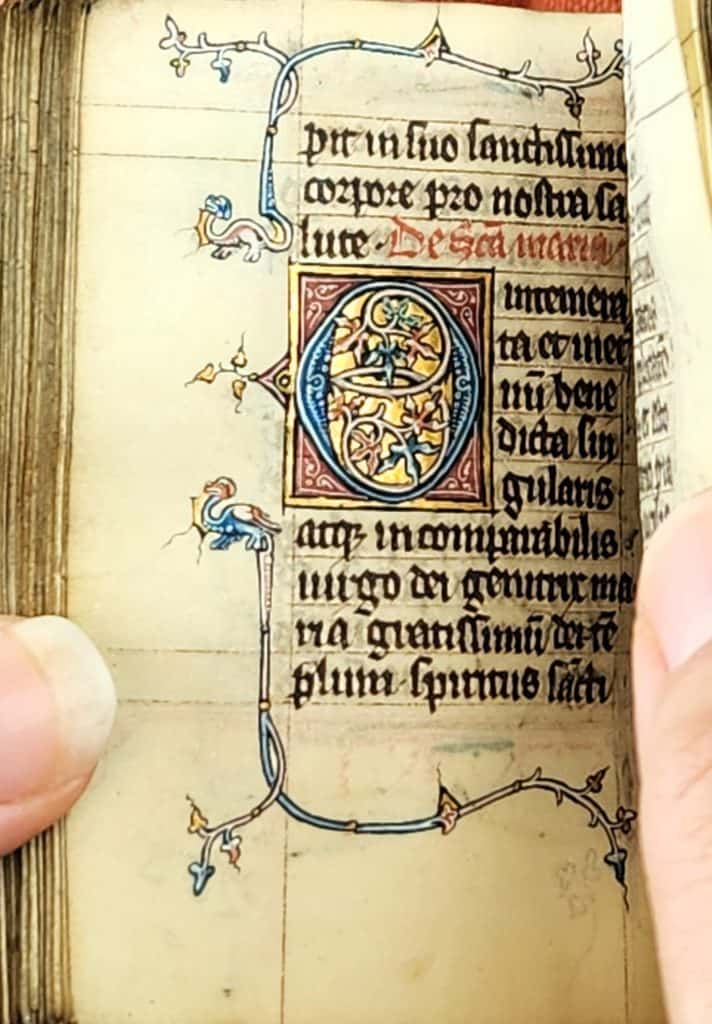

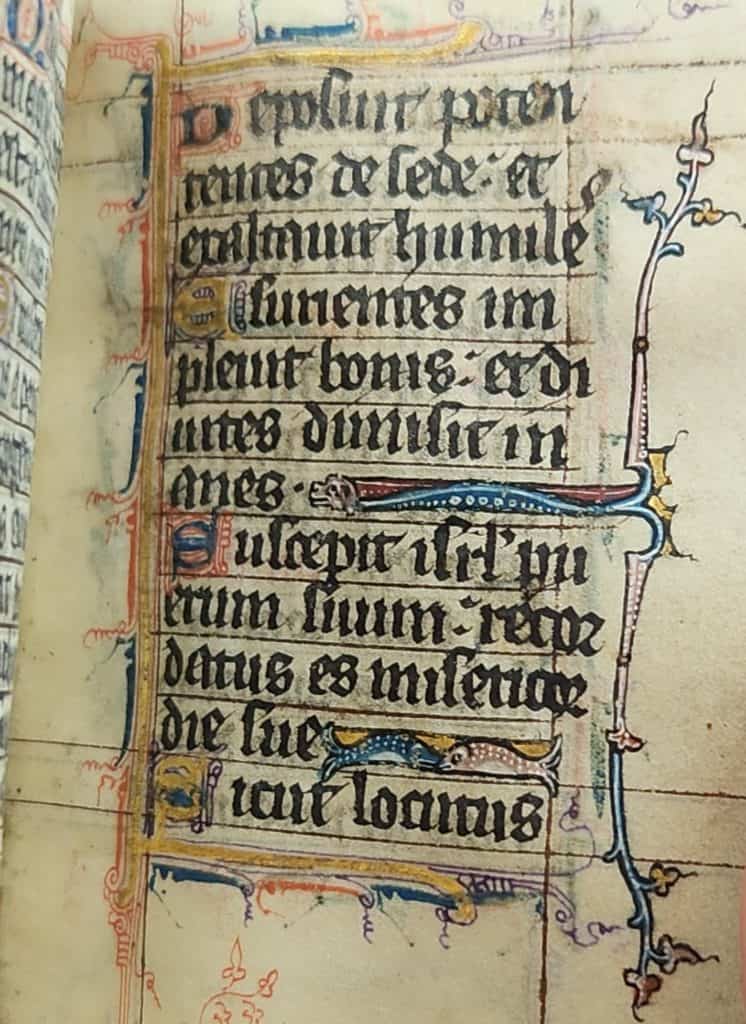

In contrast, this chant (fig. 2, xfMMs.Ps4) from an early 15th-century gradual is syllabic: except for a couple of melismas, or vocal runs, there is one neume per syllable. It’s hard to get a sense of the size, but this manuscript is about 15 inches wide. It was likely used in a church choir to allow multiple singers to cluster around it. It isn’t quite as big as some of the antiphonals in our collection, though. Terms for medieval manuscripts can be slippery, but graduals were used as part of the regular Mass, while antiphonals were used in Divine Office, the daily round of prayers in monasteries. These various collections of music were often produced for use in monasteries and cathedral churches.

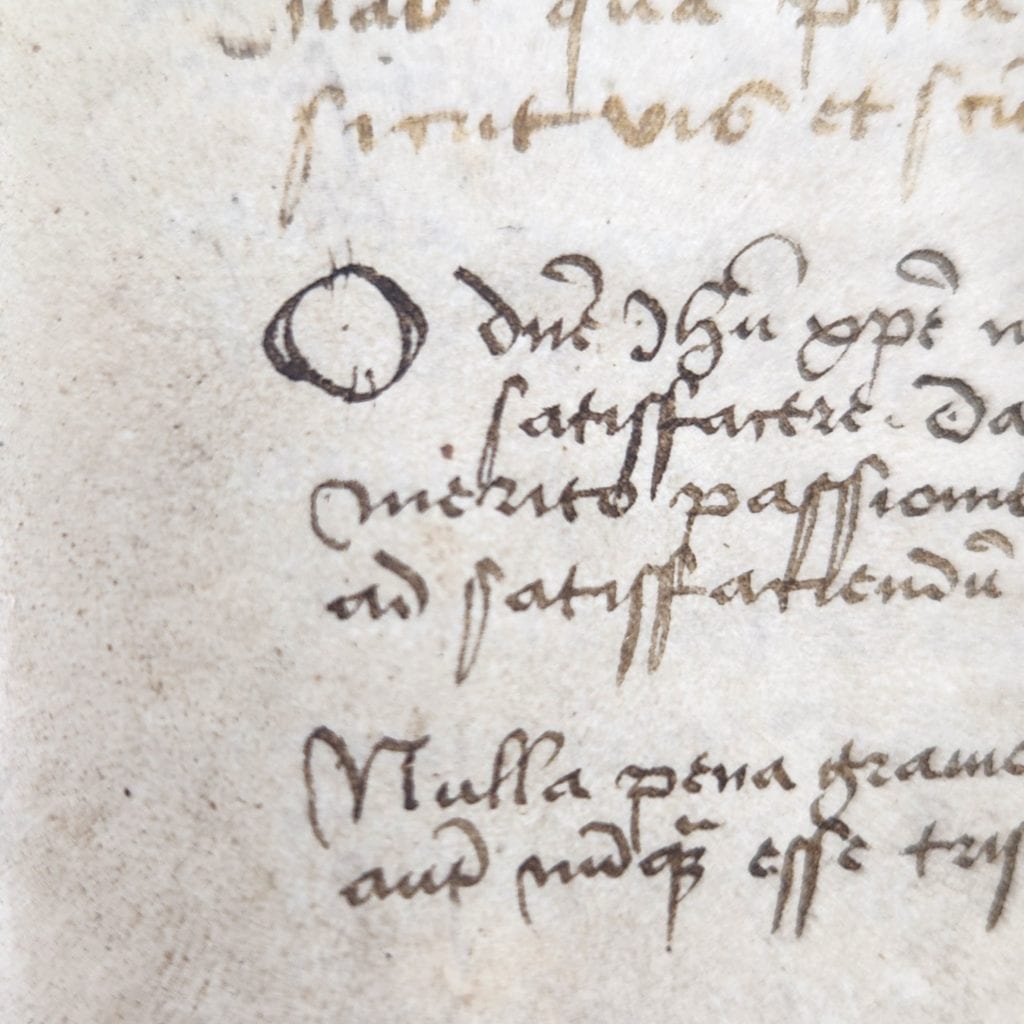

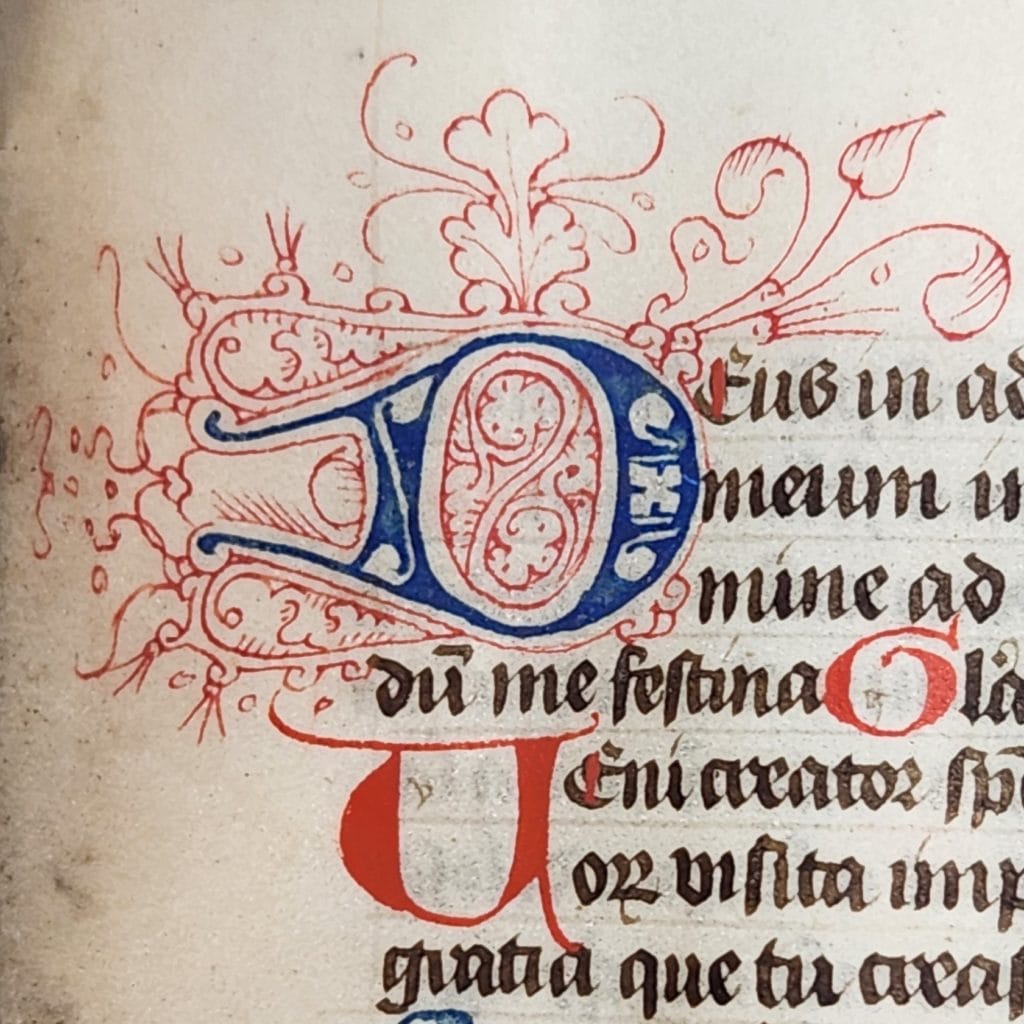

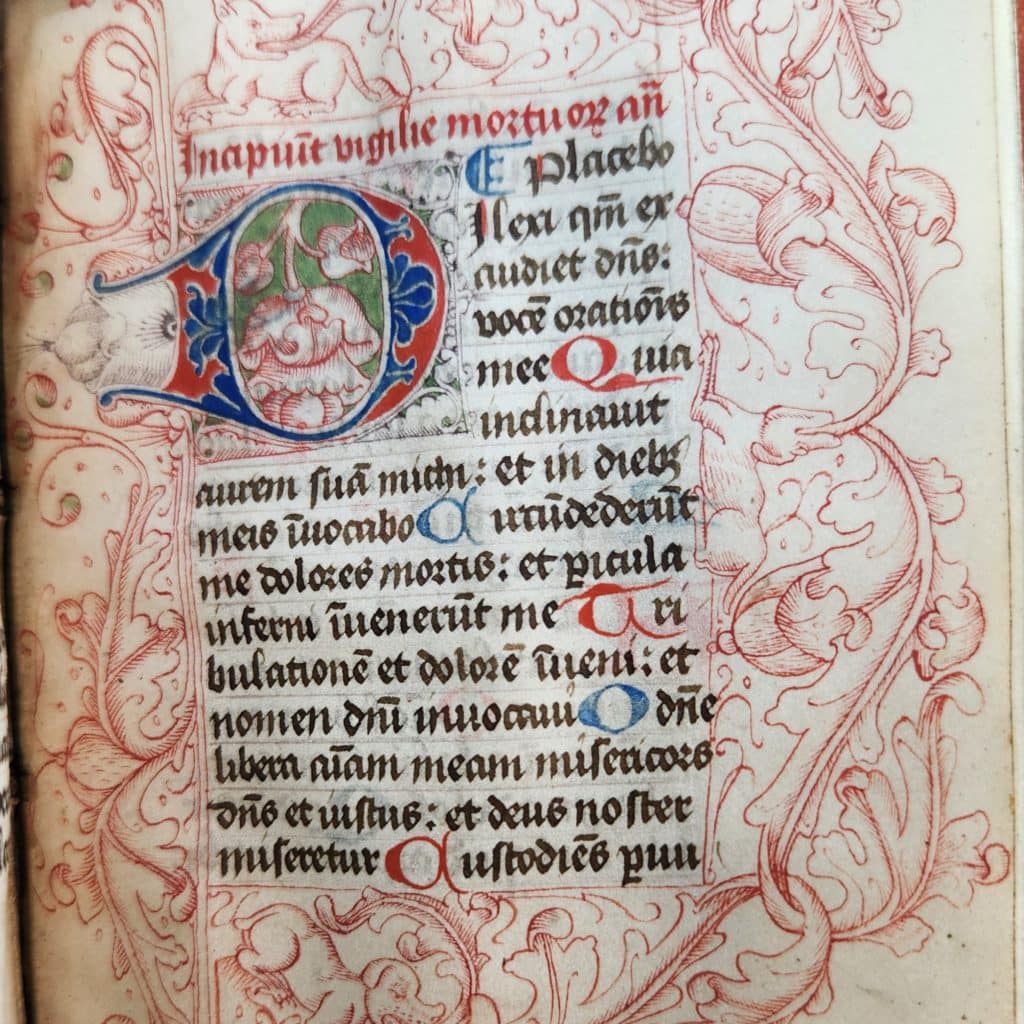

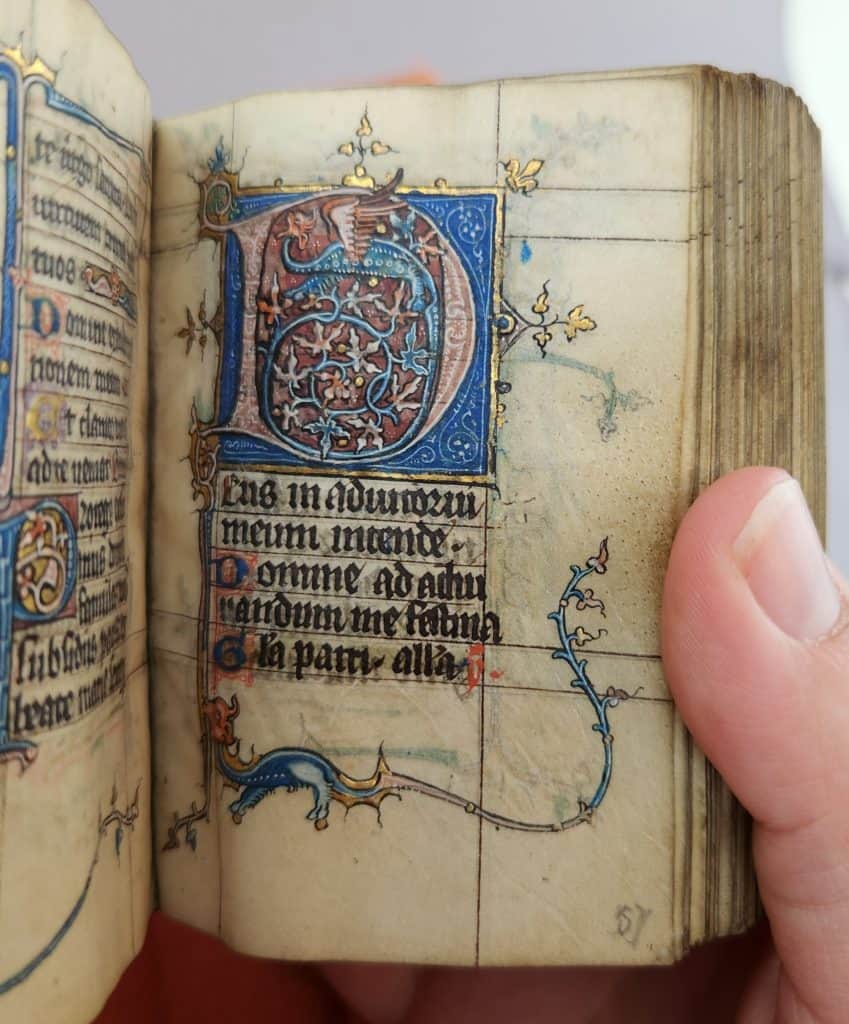

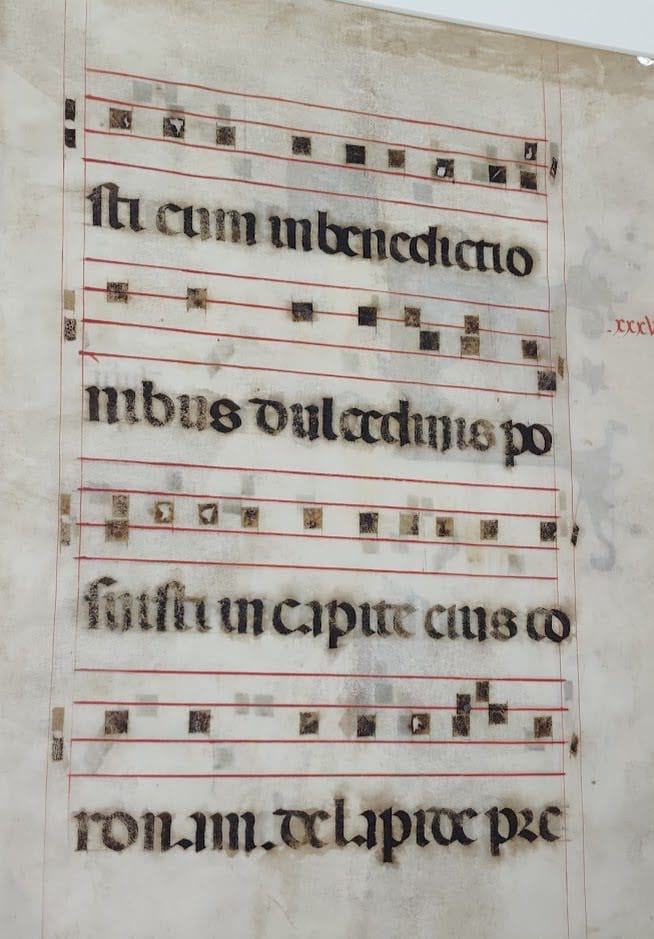

One more place you might find medieval music is in a missal, like this one from the late 14th-century Italy (fig. 3, xfMMs.Miss1). Missals compiled all the texts and instructions necessary to celebrate Mass, making them a handy reference tool or educational book. Missals might be noted or unnoted, depending on the needs of the institution for which it was produced. In this case, the scribe wrote the text first and inserted the music after. But scribes could also make mistakes.

This section of text pictured above contains an Alleluia setting that has run off the edge. You can see places where the scribe erased and rewrote the neumes to better fit the line.

The increasing use of notated chants ensured the proper performance of the Mass: no more forgetting the melody, and no more local variations of now-standardized chants. Neumes themselves would give way to more detailed methods of notation. But their history and the types of books they reside in provide a fascinating window into the musical life of the Middle Ages. View these manuscripts and more in our reading room, and learn even more about early music at the Canter Rare Book Room in the Music Library.

Works cited and further reading:

Bell, Nicolas. Music in Medieval Manuscripts. The British Library, 2001.

Crocker, Richard, and David Hiley, eds. The New Oxford History of Music: The Early Middle Ages to 1300. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Dunlap, Jennifer Rebecca. “A Paleographical Study of the Noted Missal Iowa City, University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections xfMMS.Miss1.” Master’s Thesis, University of Iowa, 2008).

Seay, Albert. Music in the Medieval World. Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1965.

xfMMs.Gr3. Leaf from a gradual., circa 1230, 8. Medieval Manuscripts, MsC0542. University of Iowa Special Collections.

xfMMs.Ps4. Leaf from a gradual., early 15th century, 8. Medieval Manuscripts, MsC0542. University of Iowa Special Collections.

xfMMs.Miss1 Missale Romanum., circa 1400, 12. Medieval Manuscripts, MsC0542. University of Iowa Special Collections.