The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Rich Dana

In the 1970s, a remarkable woman from Argentina was an underground art sensation.

While researching the forgotten art of hectographic printing, I discovered the work of Mae Strelkov, a little-known visionary artist from Argentina. This discovery was the sort of experience that illustrates precisely why those of us who frequent special collections libraries love them so much; when I followed the finding aid (M. Horvat Science Fiction Fanzines Collection, MsC0791) and opened the folder, the contents were not just a reproduction or a digital scan of some of her creations, but a nearly-complete collection of her hand-made zines, including post-marked, hand-made envelops and personal notes.

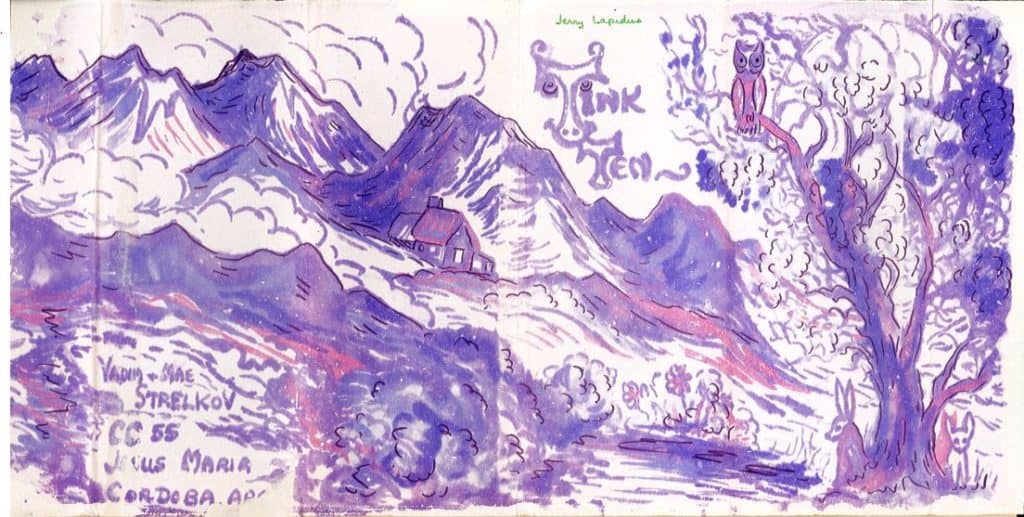

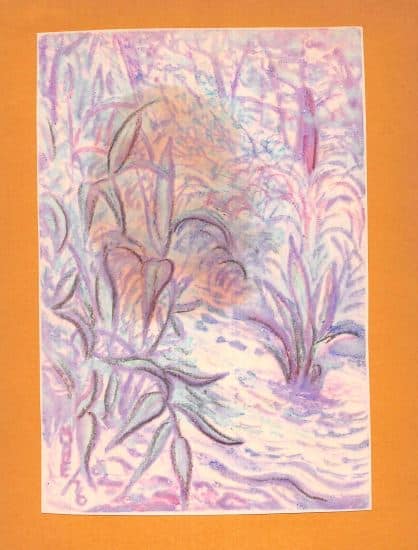

Some readers may have never heard of a hectograph. Hectography is a technique for duplicating documents using inks made from aniline dye rather than pigments. The ink is transferred to paper via a rubbery copy pad made of gelatin and glycerine, yielding up to 40 prints before becoming depleted. The hectograph was the precursor to the spirit duplicator, commonly known as a “ditto machine,” remembered for the bright purple text and sweet methyl-ester smell it produced. “Hecto” was used widely by school teachers and churches and in the production of early science fiction fanzines. It fell out of favor as newer copiers became available after WWII, making Mae Strelkov one of a handful of artists still using hectography in the 1970s.

I began to search for more information on Mae Strelkov, and found several articles written by SF fans in the early 1970s. I was also very fortunate to speak with her son, Tony Strelkov, from his home in Argentina via Zoom. Tony explained that his mother was born and raised in China, the child of English missionaries. As a teenager she met his father, Vadim Strelkov, who had fled Russia after the revolution. They married when Mae was 18 and were immediately forced to flee China to escape the Japanese invasion in 1937.

The young refugee couple found a new home in Chile, and then Argentina. In Buenos Aires, Mae worked as a translator and secretary. In 1960, Vadim was hired to manage an estancia (estate and cattle ranch) in the Cordoba hill-country of Argentina. In these beautiful surroundings, Mae raised their children, wrote and created art. Mae was an avid reader of science fiction and fantasy, and despite the isolation of ranch life, or perhaps in response to it, she became an amateur publisher, trading her zines by mail with other fans in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia. She became close friends with Donald A. Wolheim, the legendary science fiction publisher and founder of DAW books. Tony described to me the boxes, packed full of science fiction novels and fanzines, that would regularly arrive from her American friend, Wolheim.

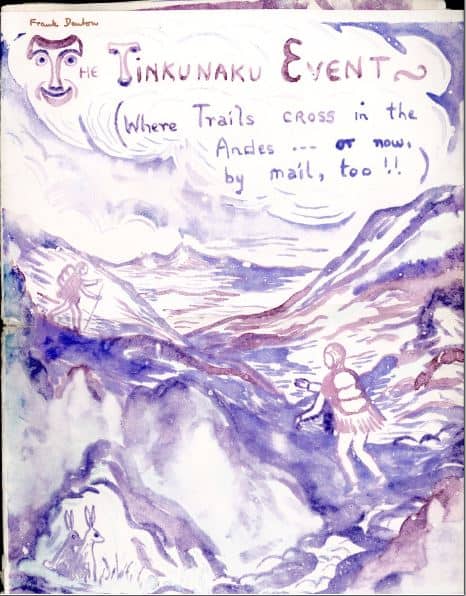

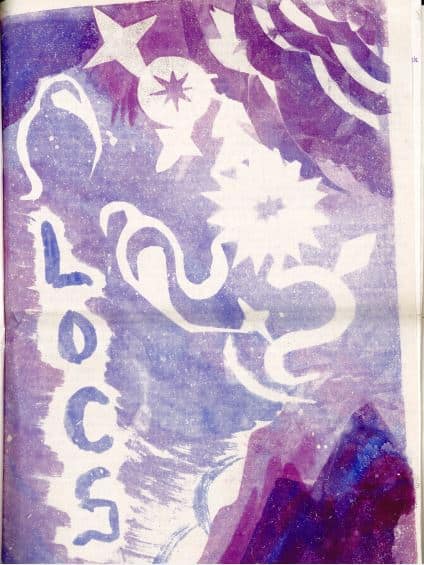

For Mae, printing options were limited for creating her publications. She settled on the hectograph, making her own printing pads (a fan legend that Tony confirmed) by boiling cow bones to extract the gelatin. Because of the limited ink colors available, her idyllic landscapes are rendered in pinks, purples, and blues, giving them a psychedelic quality. Her writings reflect on her missionary parents’ spiritual traditions, those of her childhood home in rural China, and the Andes’ indigenous people. Her landscapes are fantastical, and her accounts of everyday life on the ranch are infused with a mystical quality. Her missives are also full of observations on linguistics. She created symbols for what she considered universal human sounds– a far-out idea at the time, but one that is now widely studied among language scholars.

In 1973, Susan Wood (Glicksohn), a Canadian literary scholar/feminist/environmentalist (and SF fan) wrote in her fanzine Aspidistra:

“SF conventions, for me, exist mainly as places to meet other fannish people whom I only know on paper, people whom I have never met, who are my friends. One of those friends is Mae Strelkov…Mae has lived most of her life in Argentina, where she and her husband Vadim share a ranch with children, cattle, crazy goats, pumas—a whole world she’ll create for you with skill and zest. A talented author and an artist too, Mae is equally at home, and equally fascinating, writing about her lively family—or the world’s problems; about linguistics, and the strange pattern of words and symbols she finds repeating themselves through the oriental, western and Amerindian cultures she knows so well—or the antics of her pet skunk; about the Catholic Church, and its effects on the world as she sees it—or your latest fanzine.”

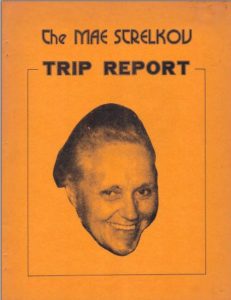

Susan Wood and Ohio fan Joan Bower mounted a successful “fan fund” (commonly used in fandom to subsidize travel for fans who cannot otherwise afford it) to fly Mae from Argentina to the US, where she would attend the 1974 World Science Fiction Convention in Washington DC (DISCON II) and DeepSouth Con in Atlanta. According to Con reports, the grandmotherly 57-year-old Strelkov made a splash with the young American con-goers. She also purchased a Greyhound Bus Ameripass and zig-zagged from coast to coast and back, visiting fans, pen-pals, and distant relatives on an epic solo adventure, all of which she recounted in The Mae Strelkov Trip Report. The 35-page report was mimeograph-printed and distributed by one of her biggest fans, NASA engineer and fanzine publisher Ned Brooks.

No description of Mae Strelkov’s writing and artwork can fully impart the actual documents’ utter uniqueness and magical quality. Unlike the vast majority of fanzines, Mae’s were produced almost entirely outside of the direct influence of American pop culture and fannish activities. For American SF fans in 1974, she must have appeared much like the character Valentine Michael Smith, a fascinating stranger in a strange land.

Mae Strelkov’s zines, as well as those created by Susan Wood and Ned Brooks, all available in the Michael Horvat Science Fiction Fanzines Collection, Msc0791.

A special thanks to Tony Strelkov for sharing his mother’s story.