The English novelist Anthony Burgess visited Iowa City in 1975 to teach at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. His course received endorsement in the “Letters to the Editor” section of the Daily Iowan. “I would like to thank the Iowa English Department for arranging such a unique class as Problems of the Modern Novel and for arranging to have Mr. Anthony Burgess teach this subject,” wrote Kevin Cookie. “I can honestly say that Anthony Burgess did present in fine form a considerable number of problems.”

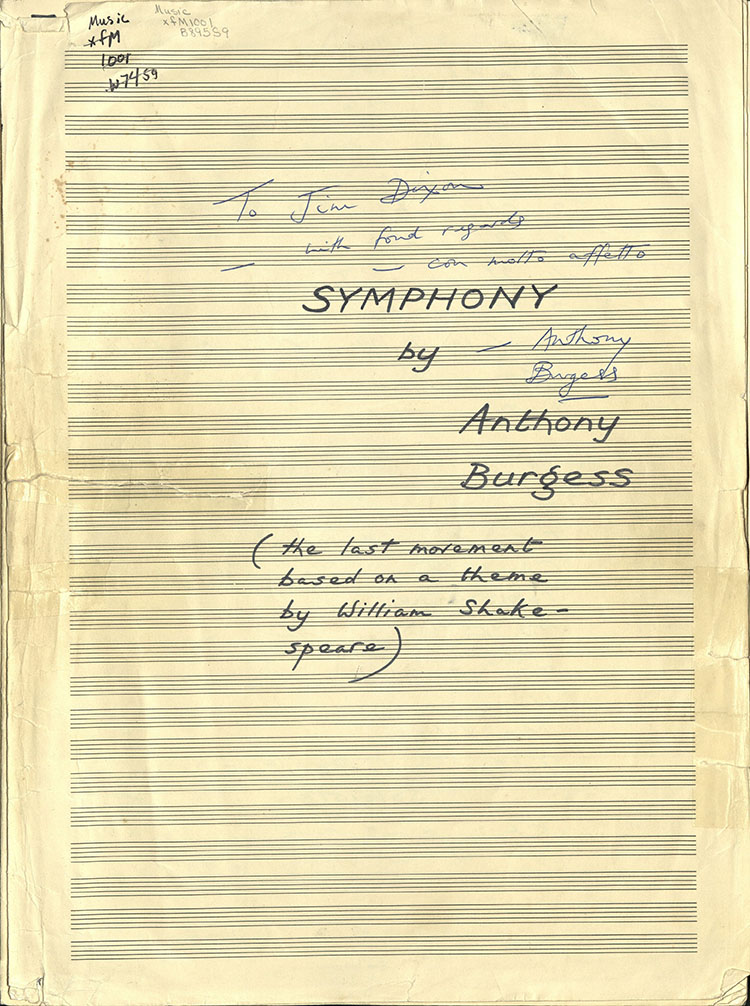

In a move that distinguished him from other visiting writers, Burgess brought with him a new symphony. He had written it specially for James Dixon and the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra.

Explained Burgess:

I’d had a long-standing invitation to visit the University of Iowa, internationally known for, among other things, its Writers’ Workshop, but something always got in the way of acceptance. Then I received a letter from Jim Dixon—not the hero of Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim but the conductor of the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra—asking me if I had anything in stock, musical of course not literary, that the orchestra might perform when, if, I came there. This seemed too good to be true. Neglect of my music by the orchestra of the Old World was what mainly turned me into a novelist, but most of this music had by now been blitzed, lost, torn up, and I had nothing in stock. So just before last Christmas I bought myself a half-hundredweight of scoring paper and starting writing a symphony.

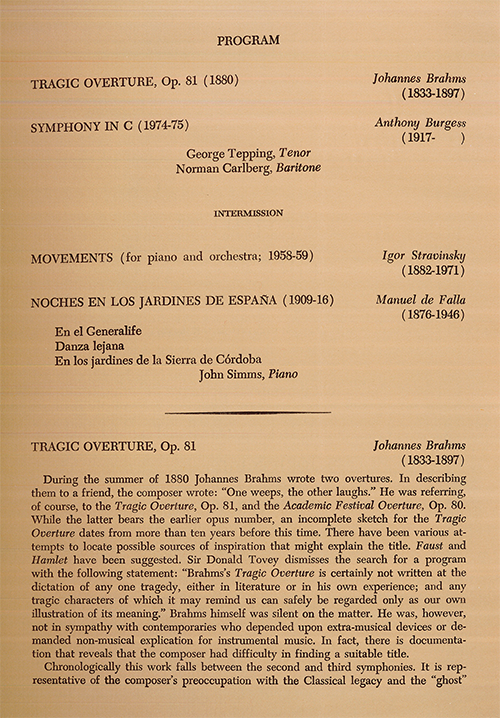

Composition of the “Symphony in C” began in Italy, around Christmas of 1974. Burgess conceded that some passages were composed under the influence of “Christmas bibulosity,” though “the writing seems sober enough.” The rest was penned during a tour of the United States, with Burgess laboring mightily midst airport muzak. “Do the people responsible for this bland abomination,” mused Burgess, “realize that there are people around desperately trying to compose music of their own?”

When Mr. Dixon brought the work before the orchestra, Burgess responded with delight: “I attended the first rehearsal and was awed at the large competence of all those delectable kids in blue jeans…I had written over 30 books, but this was the truly great artistic moment.” It wasn’t all perfect, of course. Some of what Burgess had written needed fixing. Plus, “young people do not take kindly to pianissimo markings: they like to saw or blast away.”

Not all the blue-jeaned musicians were exactly kids. The bass section included Laird Addis, who had received his bachelors and Ph.D. degrees from UI and was serving as a philosophy professor. (In addition to his forty-year tenure as a UI faculty member, Laird spent decades playing in the Quad City Symphony and cofounded the Iowa City Community String Orchestra. His passing in 2018 is keenly felt.) The violin section was helped by the presence of Candace Wiebener, another UI alumna who was by then already serving as City High School’s Director of Orchestras. (She retired in 2012 and is active in the local music scene; she also plays in the Iowa City Community String Orchestra.) Googling the names of other musicians from the program produces a vivid illustration of what happens to young musicians who train intensively together and then disperse across the country: they teach, perform, and grow musical communities.

In A Clockwork Counterpoint, Paul Phillips begins his study of Burgess’s music and music-infused writings with the Iowa City premiere of the symphony. His reason is simple: the concert affirmed within Burgess his calling to write music. This was no mere pat on the back; it was a rebalancing of the soul. Phillips notes that “unlike Paul Bowles and Bruce Montgomery, who compartmentalized writing and composing as independent activities, Burgess constantly sought ways to unite both halves of his creative personality.” It was not always easy, as demand for Burgess’s writings far outstripped interest in his many–over 250–compositions. It is telling, for instance, that Burgess compared his own exasperation over A Clockwork Orange’s rampant notoriety to a composer’s plight: Rachmaninoff, who came to begrudge audiences’ obsession with his Prelude in C# Minor. Upon hearing the UI Symphony Orchestra play his own opus, Burgess realized that Iowa City was that rare space where his talents as writer and composer might be appreciated together, where the problems of the modern novel might coexist peaceably with a new symphony: “how blessed the opportunity, however brief, to communicate without preaching, without being groused at for delivering no or the wrong message—to communicate in pure sound, form, pattern.”

Burgess left the manuscript score of his symphony—inscribed affectionately to James Dixon–with the university, where it is kept in the Canter Rare Book Room of the Rita Benton Music Library. Whatever distractions the Christmas celebrations and airport muzak posed, they have left relatively few signs of distress in the score itself, which is written neatly in ink. At one point Burgess lost or emptied his black pen, forcing an abrupt to switch to blue ink in the middle of the first movement. There are also some irreverent remarks printed in Arabic. Evidently proud of these idiosyncratic improprieties, Burgess referenced them in multiple commentaries on the symphony.

As a whole, the symphony exudes an affable eclecticism of styles, somewhat akin to the spirit of Leonard Bernstein’s concert works. Also similar to Bernstein, the music’s charismatic appeal to listeners is balanced by substantive challenges for players. No one gets off easy. Large swaths of the work flicker with rapid activity, intense contrasts in orchestral color, and rhythmically intricate handoffs. As a result, players must execute challenging passagework under very exposed circumstances. Burgess may have thought he was writing a symphony, but the players are tasked with a concerto for orchestra.

Given the sheer musical interest—and fun—of the symphony, it is surprising the work is not better known. (The symphony remains unpublished.) Dixon’s own intention to release a professional recording with the UI Symphony is a plan that remains to be realized by a future director.

Even so, Dixon’s invitation to Burgess and the composer’s enthusiastic response call us to reassess our own capacity for versatile creativity—as well as our opportunities to elicit such creativity from others. “It follows,” wrote Burgess, “that all novelists should also be symphonists and that their works should be performed in Iowa City. Good for their souls as well as for their primary craft. And it might also give them a chance to write gratefully about people like Jim Dixon and orchestras like the one he trains and conducts.”

The Story behind the Story

I learned about Burgess’s Iowa Symphony from Theodore Ziolkowski’s Music Into Fiction: Composers Writing, Compositions Imitated, which music librarian Katie Buehner helpfully displayed on the new book shelf. I checked out the book because I liked the title and then placed it carefully alongside other well-titled books in my office. When I finally got around to opening it, I was surprised to find a reference to the symphony’s premiere at UI.

A few searches in the catalog and further correspondences with Katie, Amy McBeth, and Christine Burke led to the printed program for the concert, Burgess’s manuscript score, and the university’s archival recording of the concert itself. Before seeing the score or hearing the recording, I was already hooked by Burgess’s program note, which introduced the symphony to listeners in terms that were alternately engrossing and endearingly self-deprecating. At this point, the story seemed to be taking me by the hand. Being the obliging sort, I followed.

I studied Burgess’s manuscript full score at the staff work table tucked behind the patron counter at the music library. This setup was different from my visits to collections with devoted tables for researchers. In those spaces—such as the University’s Special Collections–researchers are set up with rare materials at a large table and left to commune with their selected sources. Score study of Burgess’s symphony, in contrast, was fit alongside the daily work of student staff. My encounter with Burgess’s music happened amidst the inner workings of the library itself, as students Alex, Anastasia, Ramin, and Shelby bound new music scores, loaded book carts, and helped patrons. I liked being close to these familiar rhythms, which reminded me of working as a student employee at the University of Michigan music library. That early experience of being surrounded by music and music scholarship had helped me find my way; UI’s music library offers similar opportunities today.

And it is not a stretch to imagine Burgess approving as well, knowing that his music for Dixon and the UI Symphony contributes to the curiosity-driven economy of research, by which music-making sustains and is sustained by the efforts of staff and librarians. Burgess would be pleasantly surprised to know that the recording of the premiere has benefited from the library’s care. “The work went on to tape,” he noticed, “to be blurred by the magnetic apparatus used in airport security checks, eventually to be snarled up or to wear out or to be accidentally wiped off.” While nothing material lasts forever, the university’s records of that special Iowa City performance are for now well kept at the Rita Benton Music Library, where ongoing efforts to enliven local history—including historic premieres by our student ensembles—provide current students with means to pursue music studies and designs of their own.

Select Bibliography

Burgess, Anthony. “A Clockwork Orange Resucked (1986).” In A Clockwork Orange. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1962, 1986.

Burgess, Anthony. “How I Wrote My Symphony.” New York Times. 28 December 1975, 73.

Burgess, Anthony. “Symphony in C.” Note published in the University Symphony Orchestra program. 22 October 1975.

Cookie, Kevin. “Burgess as Teacher.” Daily Iowan. 31 October 1975.

Phillips, Paul. A Clockwork Counterpoint: The Music and Literature of Anthony Burgess. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

Ziolkowski, Theodore. Music into Fiction: Composers Writing, Compositions Imitated. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2017.

Image credit: “Anthony Burgess en 1986.” Zazie44, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

About the Author

Nathan Platte’s research and teaching interests include American film music, opera, collaborative creativity, and musical adaptations across media. He has presented papers at national and international conferences, including the Society for American Music, Society for Cinema and Media Studies, the American Musicological Society, and the British Library. His articles and projects have received recognition from the University of Michigan (Louise E. Cuyler Prize in Musicology), Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center (Dissertation Fellowship), the American Musicological Society (Publication Subvention), and Society for American Music (Mark Tucker Award and Wiley Housewright Dissertation Award).

Platte’s publications explore film music of Hollywood’s studio era from a variety of angles, including the collaborative process of film scoring, the intersection of technology and music, the role of studio orchestras, and soundtrack albums. His articles have appeared in many journals, including The Journal of Musicology, 19th-Century Music, and The Journal of the Society for American Music. Platte’s work has also been published in anthologies, including Music in Epic Film: Listening to Spectacle (Routledge, 2017), where he contributed an essay on the Tara theme from Gone With the Wind, and Sound: Dialogue, Music, and Effects (Rutgers University Press, 2015), to which he contributed a chapter on production practices in postwar Hollywood. Platte’s books include The Routledge Film Music Sourcebook (Routledge, 2012; coedited with James Wierzbicki and Colin Roust) and Franz Waxman’s “Rebecca”: A Film Score Guide (Scarecrow Press, 2012; coauthored with David Neumeyer). His most recent book, Making Music in Selznick’s Hollywood (Oxford University Press, 2018), investigates the scores for films like Gone With the Wind, Since You Went Away, and Spellbound.

Platte received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, where he also completed bachelor’s degrees in history and trombone performance. Before joining the faculty at the University of Iowa in 2011, he taught at Michigan and Bowling Green State University.