This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Brianna Bowers, student worker for Special Collections and Archives.

Have you ever made a New Year’s resolution or used the turning of the calendar to wipe a clean slate for yourself? These resolutions can be effective at creating new habits, but what about when you need to rethink the philosophical underpinnings of your whole life? Or what if you are not actually an individual, but a whole country

If you are France during the French Revolution of 1789, then you are experiencing a massive shift from absolute monarchism to republicanism. Enlightenment values such as reason are in, and monarchical and religious tradition are out. The government is determined to recreate itself according to these new principles. That includes reworking its systems, such as systems of measurement. Measurement is used every day in the arts and sciences, which are the bread and butter of an Enlightenment-influenced revolutionary. So, it is crucial that they are logical and patriotic, after all.

As a result of this, the revolutionary government designed and adopted the metric system. We can all breathe a sigh of relief that a meter is 1/1,000th of a kilometer, 100 centimeters, and 1,000 millimeters. It is clean, orderly, and logical. It is obviously so scientific that even in the United States, where we usually use the customary system, students in science classrooms measure in metric.

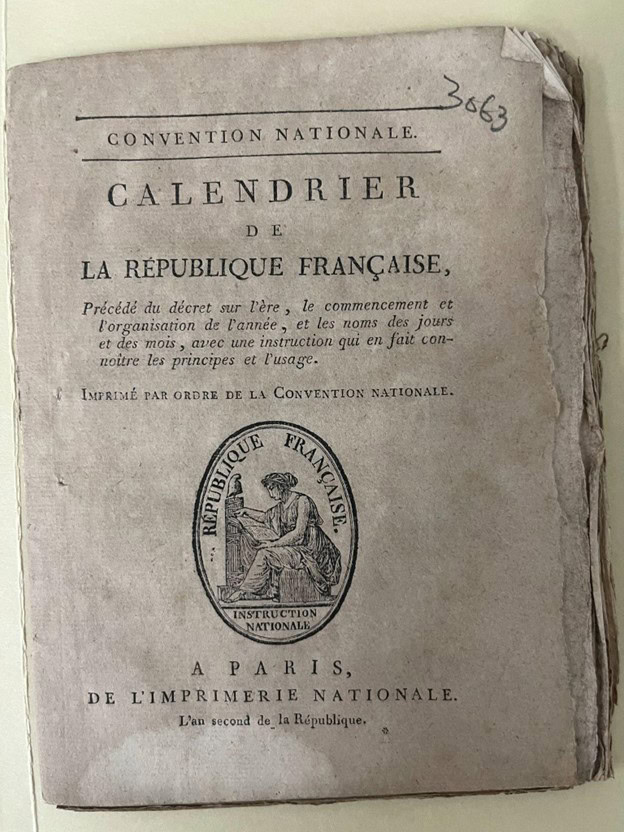

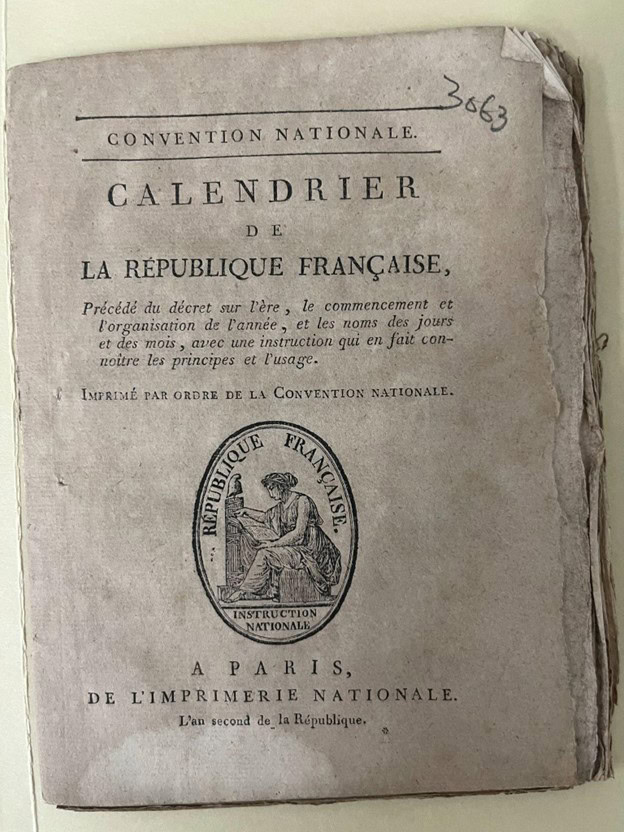

But did you know that the revolutionary government also created and used a new calendar? In the Main Library Special Collections and Archives, we have a pamphlet called “calendrier de la république française” (Calendar of the French Republic) printed by the governing legislature of France, the National Convention, that explains this new creation.¹ It cites exactitude, simplicity, independence from religious practices, and reason—a character that suits the Revolution—as important traits of a calendar (pages 8 and 19), and describes how the new French Republican calendar met those goals.

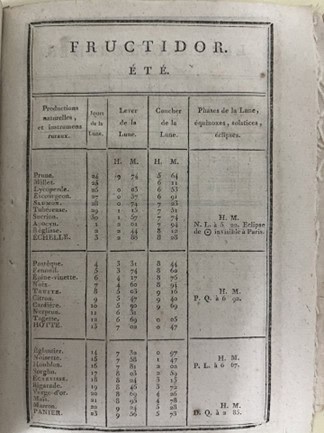

The French Republican calendar did not have some months with 30 days, some with 31, and one with 28 or 29. No, every month of this new calendar, named after its climate and agricultural stage as experienced in the northern hemisphere, had exactly thirty days. Each month was split into three weeks with 10 days each. No week spilled over between months. The days of the week were named after the words for first, second, third, and so on. Within a day, there were ten hours, each hour had one hundred minutes, and each minute had one hundred seconds. (However, the unique hours, minutes, and seconds were not widely used. Their use was made non-obligatory on April 7, 1795.³) It was simple and logical, right?

The extra days at the end of the year were used for Revolution-themed festivals. Instead of the Christmas Eve to New Year’s festivities, you’d get the Sanculotides. The term Sanculotides comes from the sans-culottes, the urban working class of Paris which supported the Revolution. The festivals were for virtue, talent, labor, convictions, and honors, and the leap day attached to the end of the year was Revolution Day.⁴ The years counted up from the all-important establishment of the First French Republic. Crossing off dates and flipping your calendar month was now a patriotic act.

If you were a citizen of France when this calendar was in use, you would not make your New Year’s resolutions on the first of January. As the revolutionaries explained in their pamphlet, most civilizations making calendars use seasonal changes or remarkable historical events to fix the date of the changing of the year. (They sharply criticized Charles IX for adopting an illogical calendar, which doesn’t start on one of these natural dates, just because everyone else was doing it (page 10¹)!) The first day of the first month of the French Republican Calendar starts on the fall equinox. The first month is named Vendémiaire, after the grape harvest. Vendémiaire is followed by Brumaire (the foggy month), Frimaire (the cold month), and then the three winter months of Nivôse (the snowy month), Pluviôse (the rainy month), and Ventôse (the windy month). Next are the spring months of Germinal (the developing of sap month), Floréal (the flowering month), and Prairial (the meadow harvest month). The final months are the summer months of Messidor (the wheat harvest month), Thermidor (the hot month), and Fructidor (fruits’ month). The calendar was officially used from the 15th of Vendémiaire, year II of the French Republic, to the 10th of Nivôse year XVI (Oct. 6, 1793, to Dec. 3, 1805).²

This means that the French Republican year CCXXXIV is beginning this Sept. 22! If you want to start your resolutions on Vendémiaire first, you had better get a move on.

———

¹ Pamphlet 3063 in box 3057-3114, “Convention nationale. calendrier de la république française, Précédé du décret sur l’ère, le commencement et l’organisation de l’année, et les noms des jours et des mois, avec une instruction qui en fait connoître les principes et l’usage. Imprimé par ordre de la Convention nationale.” In the University of Iowa Main Library Special Collections [or read it online at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k48740w/f9.item].

² https://www.napoleon-empire.org/en/republican-calendar.php. The site has lots of good information and a handy calendar converter.

³ Page 7 of pamphlet 3065 in box 3057-3114, “Loi Relative aux poids et mesures. Du 18 Germinal, an 3.ᵉ de la République française, une et indivisible.” In the University of Iowa Main Library Special Collections [or read it online at https://www.taieb.net/auteurs/poidsmes/1795_04_17_loi.html]

⁴ For the festival name translations, see https://everything.explained.today/Sansculottides/