This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Calvin Covington, Olson graduate research assistant.

I’d wager that, even if they haven’t gone to a game, most of Iowa City’s population has borne witness to the grand Kinnick Stadium, where, every football season, legions of fans flock to watch the Hawks battle their Big Ten rivals in one of America’s favorite games. It’s hard to imagine Iowa City gamedays without swarms of tailgate traffic. However, a century ago, Iowa’s iconic stadium was just a glimmer in the eyes of its athletics department, and it would be a long journey to the Kinnick name.

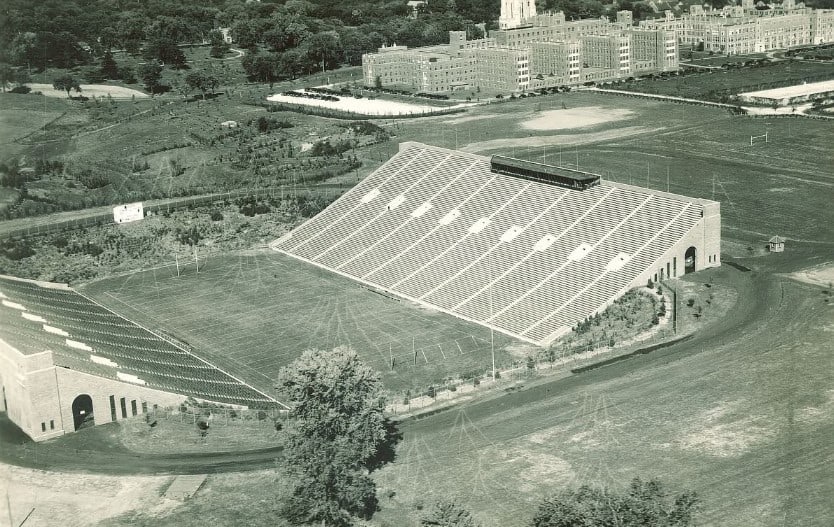

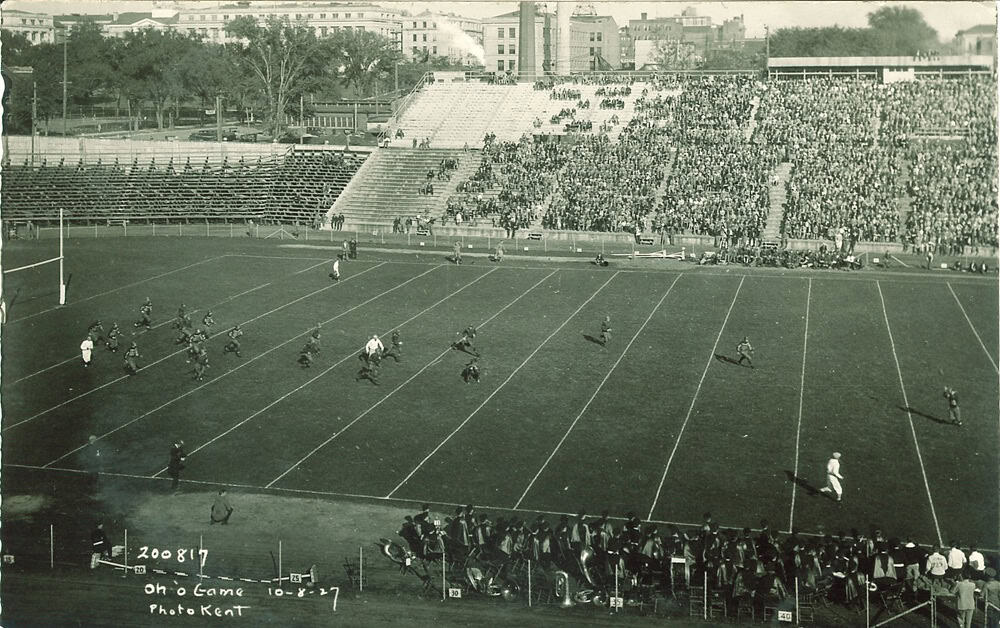

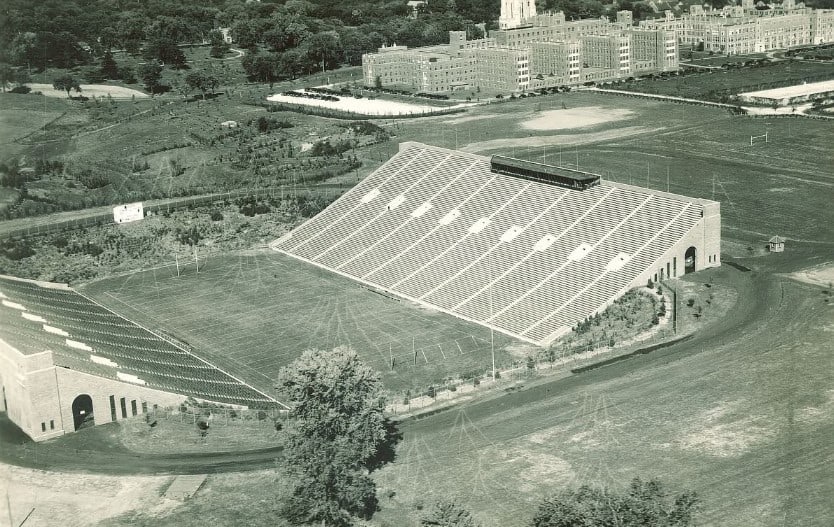

Before Kinnick Stadium, the Hawkeyes had Iowa Field, a somewhat plainly named stadium with a capacity of 30,000 (less than half the size of modern-day Kinnick), located not on the west side of campus, but on the east side behind the Main Library. You can even see the Pentacrest in the photo below.

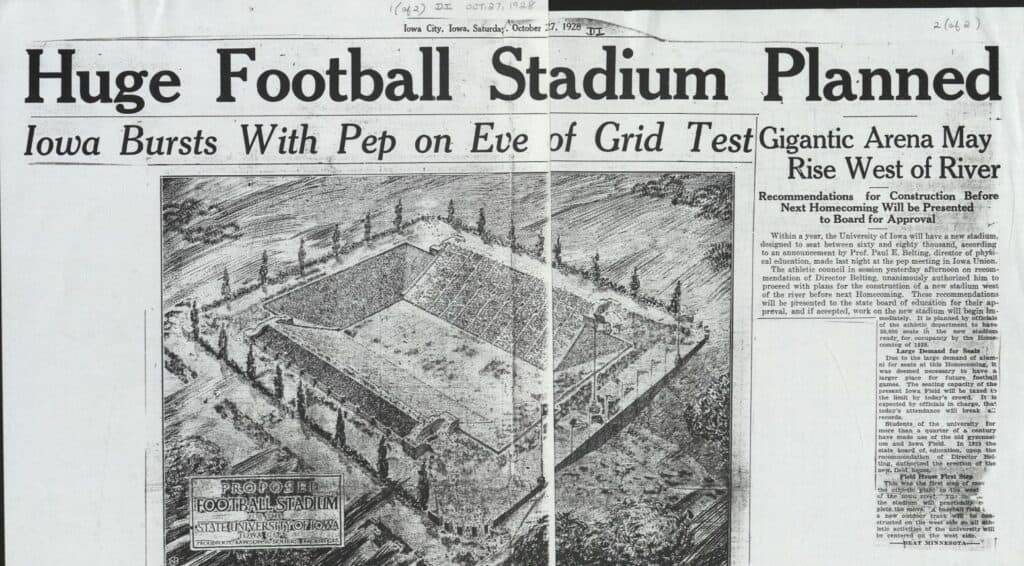

A century ago, the athletics department wanted a new field, but building a new, larger venue was not an easy task. The stadium was constructed over a period of about seven months during 1929, totaling $484,798, or over $9 million today. Being built a century ago in a rural state, horses and mules (as seen below) were used to excavate and pull heavy equipment, and workers toiled day and night until completion in October 1929.

During the construction, Iowa’s third athletic director, Paul Belting, resigned and the new director, Edward Lauer, was told that Iowa would be suspended from the Big Ten in January 1930 due to recruiting violations. Despite these difficulties, Lauer got the Big Ten decision rescinded in February, and Iowa re-entered the Big Ten with its brand-new stadium—called Iowa Stadium.

But this name lacked inspiration and a legacy. Nile Kinnick, born in 1918, wasn’t even in high school when Iowa Stadium construction was completed. After a historic career, ending with the 1939 Heisman trophy, Kinnick went to law school and coached for a year before enlisting in the Naval Air Reserve, where he would ultimately perish in a training flight off the coast of Venezuela at age 24. After the tragedy, the student body held a vote in 1945 to name the stadium “Nile Kinnick Memorial Stadium.” And then, nothing happened.

The vote was unofficial, and the name didn’t change. In fact, Iowa can’t even claim the first Kinnick stadium. That honor would go to the Meiji Jingu Gaien Stadium in Tokyo, Japan, which was renamed in 1945 by the U.S. occupation force to “Nile Kinnick Stadium.”

It was only, nearly three decades later, in 1972, that support for renaming the stadium drummed up again. Beginning with attorney L. E. Swanson and spreading through the newspapers, the support for the name eventually reached the university administration and President Willard Boyd, who, after some consideration (including deliberations on naming the stadium after both Iowa football stars Kinnick and Duke Slater, who played from 1918–1921 at Iowa, was the NFL’s first Black lineman, and became Chicago’s second Black judge), approved the name change. By the end of the year, “Kinnick” became the official name.

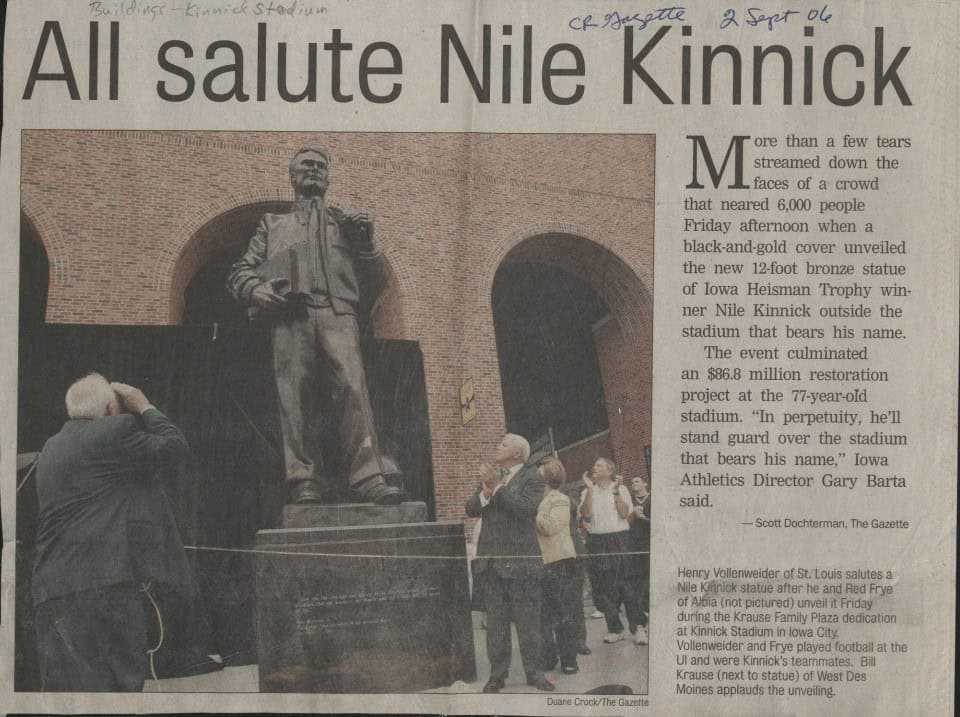

Over the years, Kinnick Stadium has changed a lot. Renovations and expansions since 1929 have far exceeded the initial cost of the stadium, including the $86.8 million restoration project in 2006, culminating in the iconic Kinnick statue that now stands in front of the stadium. Many features of the stadium, from the seats to the scoreboard to the grass of the recently named Duke Slater Field (2021), have all been replaced in the years since. So, next time you go to a football game, think about how much the stadium around you has changed, and consider the ways the devoted fans have remained the same.

Visit Special Collections and Archives to learn more about Nile Kinnick and the stadium named after him. Plan your visit on our website.