It’s July and time for a beloved week in television: Shark Week. These sleek, weird, and beautiful apex predators are mesmerizing and also a little terrifying. But what do sharks have to do with medicine?

Surprisingly, quite a bit—thanks to Elementorum myologiae specimen [A Sample of the Elements of Myology] (1667), a work by 17th-century Danish physician, geologist, and Catholic bishop Niels Steensen (Latinized as Nicolaus Steno). His life and work gave us the anatomical-geological mashup we didn’t know we needed.

Born in Copenhagen in 1638, Steensen’s early life was marked by fragility and curiosity. Surviving a mysterious illness of his own at age three, he grew up during a time of plague. The 1654–1655 outbreak claimed 240 of his schoolmates, a tragedy that likely shaped his deep interest in the natural world.

Educated in the classical sciences, Steensen wasn’t one to accept inherited wisdom. By 1659, he was already challenging long-held beliefs, questioning everything from the origin of tears to the nature of fossils.

Steensen began his medical studies at the University of Copenhagen. Encouraged by his anatomy professor Thomas Bartholin, he set off across Europe to study with the best minds of the time. His journey took him from Rostock to Amsterdam, Leiden, France, and finally Italy.

In Amsterdam he studied under Gerhard Blasius. There, he made his first major discovery: the parotid salivary duct, now known as the Stensen duct. His meticulous dissections of animal heads revealed previously unknown structures, culminating in his 1662 publication Observationes anatomicae, which redefined the anatomy of the salivary glands.

His anatomical work didn’t stop there. While studying cow hearts, Steensen came to a radical conclusion: the heart, long thought to be the seat of the soul and source of innate heat, was simply a muscle. In De musculis et glandulis (1664), building on William Harvey’s De motu cordis (1628), he boldly declared, “The heart…is nothing more than muscle,” challenging centuries of Galenic and Aristotelian doctrine.

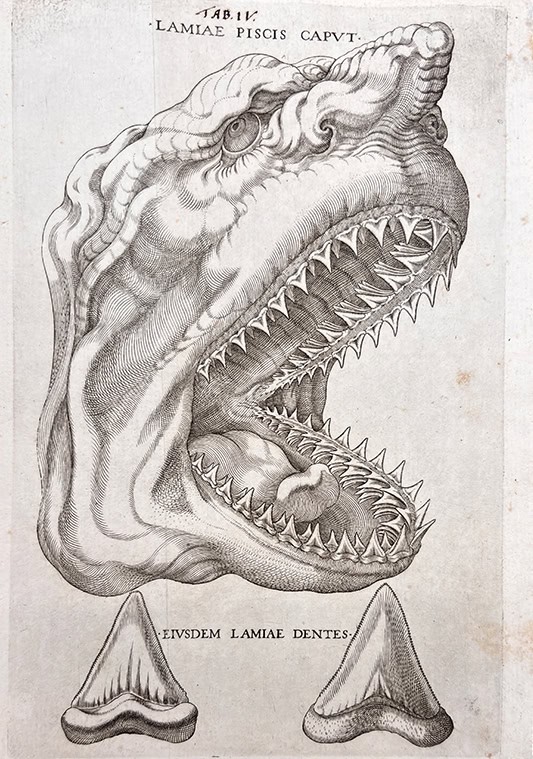

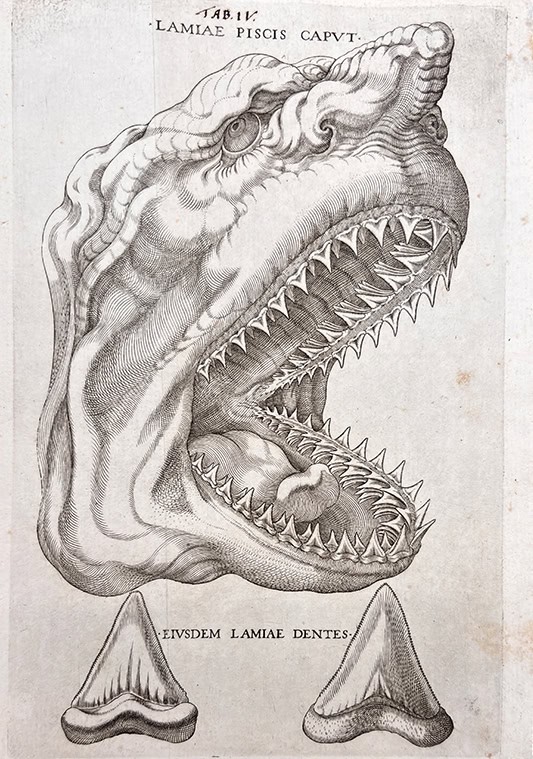

It was in Italy in 1666 that Steensen had a fateful encounter with a shark. This moment would deepen his anatomical studies and spark a new scientific passion that helped lay the foundations of modern geology.

A massive shark was caught near Livorno, and its head was sent to Steensen by order of Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici. During the dissection, Steensen noticed something striking: the shark’s teeth looked exactly like “tongue-stones”—fossilized objects found far inland, long believed to be petrified dragon tongues. This observation sparked a new obsession: geology.

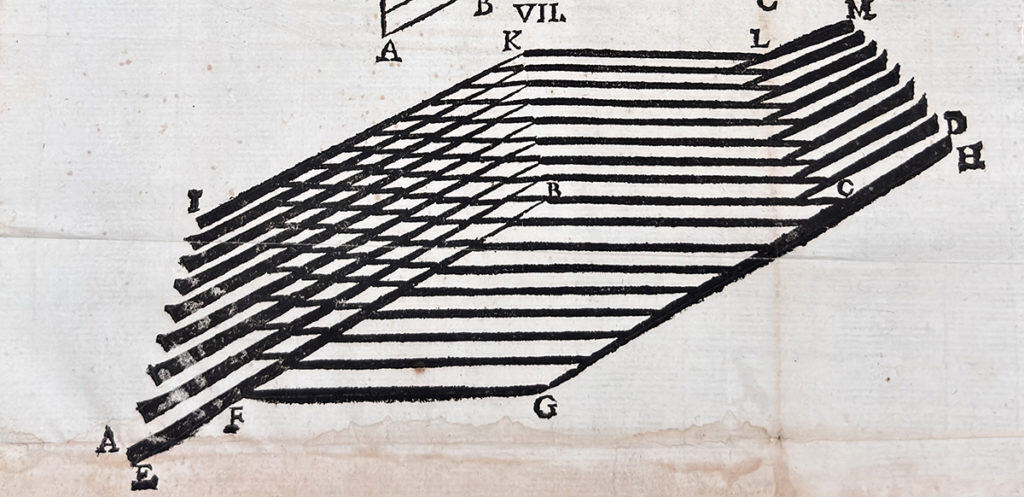

Steensen’s genius lay in his ability to connect disciplines. His insight—that fossils were once-living organisms embedded in rock—led to foundational principles in geology. In De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento (1669), he laid out ideas that remain central to the field today, including the law of superposition and the concept that Earth’s layers tell a readable history.

Despite his scientific achievements, Steensen’s life took a spiritual turn. In 1675, he became a Catholic priest and later a bishop. He served in various cities across northern Germany, embracing a life of poverty and religious devotion. He died in Schwerin in 1686 at just 48 years old. In 1953, during a canonization process, his remains were exhumed, though his cranium was mysteriously missing. In 1998, Pope John Paul II beatified him, honoring both his piety and his scientific legacy.

Our copy of Elementorum myologiae specimen is bound in limp vellum over paper boards. The cover has contracted over time, giving it a pronounced bow. The text block is made of sturdy paper with minimal foxing or staining. A few sections remain unopened at the top, untouched since the 17th century. And the smell? A sweet, cheesy aroma that might sound off-putting, but is oddly pleasant.

∼FIN∼

TENO, NICOLAUS (1638-1686). Elementorum myologiae specimen. Printed in Florence by “the printing house under the sign of the Star“, 1667. 25 cm tall.

Contact the John Martin Rare Book Room curator, Damien Ihrig, to see this book at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.